He attempted “to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach the Congress of the United States.”

He delivered “with a loud voice, intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues, and has uttered loud threats and bitter menaces, against Congress [and] the laws of the United States, amid the cries, jeers and laughter of the multitudes.”

He has brought the “high office of the President of the United States into contempt, ridicule and disgrace.”

Johnson’s deep-rooted racism, along with his verbal excoriation of his congressional foes as “treasonous” — something our current president has also done — led to his impeachment.

Sound like someone we all know? These charges certainly describe President Donald Trump’s deplorable behavior and its effects on Congress, the presidency, and — most importantly — the divisions he has exploited and widened among the American people, as well as the damage he has caused to America’s standing and role in the world community.

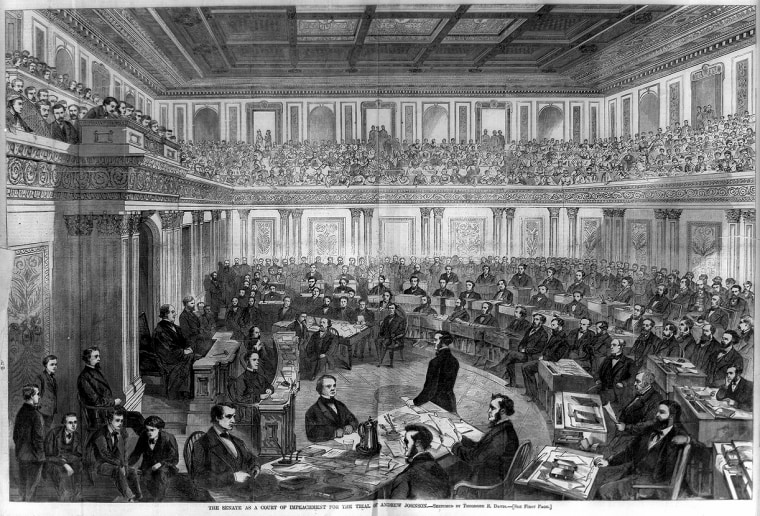

But they aren’t an imaginary list of offenses compiled by Congress to hold Trump accountable for his transgressions; they are actual excerpts from Article 10, the most important of the 11 impeachment articles brought by Congress against an earlier president: Andrew Johnson.

Johnson’s deep-rooted racism, along with his verbal excoriation of his congressional foes as “treasonous” — something our current president has also done — led to his impeachment in 1868. Article 10 of his impeachment indictment provides a legal basis and historical precedent for making a president’s racist speech an impeachable offense, by itself, as evidence of unfitness to hold the highest and most powerful office in the land.

Article 10 provides this basis by making clear that speaking contemptuously about Congress and its members, with “intemperate” and “inflammatory” attacks based on racial animus — as both Johnson and Trump did on multiple occasions — brings the presidency into “contempt, ridicule and disgrace.”

The House of Representatives would have a more solid and easily provable case for Trump’s impeachment if it immediately opened proceedings along these lines rather than continue to weigh the more complicated and legally fraught obstruction issue.

Several of the remaining articles brought against Johnson, a Tennessee slave owner and Lincoln’s second vice president, had their roots in his racism. For instance, he was charged with unlawfully firing officials — including Secretary of War Edwin Stanton — who supported Reconstruction measures to aid the former slaves and give them civil rights, and who opposed Johnson’s lenient policies toward the former Confederate states and their military and political leaders, returning them to power. Johnson was also charged with attacking pro-Reconstruction members of Congress in “intemperate” words, accusing them of “diabolical and nefarious” plots against him.

Even during the Civil War, serving under Lincoln, Johnson expressed his racist views in revealing language: “I am for this Government with slavery under the Constitution as it is,” meaning its pro-slavery provisions. And this: “If blacks were given the right to vote, that would place every splay-footed, bandy-shanked, hump-backed, thick-lipped, flat-nosed, woolly-headed, ebon-colored in the country upon an equality with the poor white man.” It was these racist words, along with Johnson’s verbal excoriation of his congressional foes as “treasonous,” that led to Johnson’s impeachment.

Like Johnson, Trump is a racist. It’s clear that the president has singled out black, Hispanic and Muslim members of Congress for “ridicule” and “contempt” by his credulous white base. He has called California Rep. Maxine Waters, who chairs the House committee trying to get Trump’s financial records, “a low-IQ person.” His racist attacks on the four freshmen congresswomen of color who call themselves “the squad” — telling them to “go back” to countries to which, as native-born and naturalized American citizens, they owe no allegiance — have been evident to anyone with eyes and ears.

Most recently, on Saturday, Trump lashed out at African American Rep. Elijah Cummings, who chairs the House Oversight Committee and whose subpoenas for White House documents and staff Trump has directed recipients to ignore: Cummings’ Baltimore district “is a disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess,” Trump tweeted. “No human being would want to live there,” he added. He really meant that no white person would want to live in Cummings’ largely black district; that racist dog-whistle was loud and inflammatory. And the president’s contempt of and toward Congress, especially its minority members, is clear in his many harangues against them.

But don’t take my word that Trump’s a racist, since I’ve said this from the moment he glided down the golden escalator and smeared Mexicans as “criminals” and “rapists.” I’ll let those who have supported him make the case: Former House Speaker Paul Ryan called Trump’s charge that a federal judge of Mexican heritage was “biased” against him “the textbook definition of a racist comment.” South Carolina Sen. Lindsay Graham labeled Trump “a race-baiting, xenophobic religious bigot” (although Graham has since repented and been welcomed back into the Church of Trump). Rep. Will Hurd of Texas, the only black House Republican, denounced Trump’s multiple tweets against the squad as “racist and xenophobic.”

Given Trump’s lifelong pattern of racist speech and behavior, I think an impeachment inquiry is required by the Constitution, for an obvious (at least to me) reason: By definition, an overtly racist president cannot obey his (or her) constitutional oath to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” Presidents are free to oppose and criticize laws passed by Congress, even over their vetoes, but not to frustrate or block their execution for reasons of racial animus.

Many of the laws Trump has sworn to enforce, enacted under the expansive legislative power given Congress in the Constitution’s Article 1, place limits on presidential power, limits the Supreme Court has recognized in several landmark cases, but that Trump disputes, arguing the grant of “executive power” in Article 2 means that “I have the right to do whatever I want as president,” as he said last week.

That’s an astonishing claim of authoritarian rule, unchecked by Congress and the courts; married to his bigotry, that’s a toxic and dangerous brew. Other laws, enacted to protect racial and ethnic minorities (and women and LGBTQ Americans) from discrimination, have been undermined or ignored by Trump and those charged with enforcing them.

The fact of almost-unanimous Republican opposition to impeachment has made it more unlikely, especially since the long-awaited and over-hyped Mueller hearings provided no new evidence of Trump’s crimes, that House Democrats will push Speaker Nancy Pelosi to abandon her slow-as-molasses approach to impeachment for Trump’s obstruction of justice, documented in the largely-unread Mueller Report.

Pursuing the president over his racism is a more promising path. His words and behavior match exactly the charges brought against Johnson in Article 10 of his indictment. A majority of the public (54 percent in the most recent Politico poll) agrees that Trump is a racist; most of the rest, I believe, either share his racist views but deny that to pollsters, or are willfully ignorant.

How long should the American people endure a president whose racism poses a “clear and present danger” to the “equal protection of the laws” guaranteed to “all persons” by the Constitution?

Placing him on trial before the House Judiciary Committee, even in absentia, with witnesses to testify and document the decades-long evidence of his racism and its damaging effects on America’s institutions and its people, might (with testimony more revealing and compelling than former special prosecutor Robert Mueller’s terse and halting answers to questions about Trump’s documented obstruction of justice) lift that number high enough to prod now-reluctant House Democrats to join the 100-plus who already support impeachment.

The fact that Johnson escaped Senate conviction and removal from office is not essential to my argument; he was crippled and ineffective in his two remaining years in office. Sure, the GOP-controlled Senate wouldn’t convict Trump, but the fact of his impeachment and the evidence of his racism would, I think, similarly cripple his efforts to stand “above the law” in pursuing his racist agenda.

Those who counsel waiting until November 2020 to remove Trump at the ballot box should ask themselves this question: How long should the American people endure a president whose racism poses a “clear and present danger” to the “equal protection of the laws” guaranteed to “all persons” by the Constitution? In my opinion, one day is too many.