I have been an ICU nurse for 17 years. I never thought I'd leave. Now I'm not sure I'll ever go back.

I've been on the front lines of Covid-19 since it broke out eight months ago. More than 250,000 people have now died in the United States. Case numbers are rising in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. And health care workers like me are burning out.

I'm exhausted. I'm angry. I'm sick of watching patients die. I'm tired of comforting families feeling guilty over the birthday party that cost their loved one's life.

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump spends his weekends golfing, and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell sent the Senate home for Thanksgiving vacation a day early, even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just advised against holiday travel.

I wish medical workers could take vacation days, too. I ran out of those months ago, when I contracted Covid-19 treating patients in the ICU. I'm exhausted. I'm angry. I'm sick of watching patients die. I'm tired of comforting families feeling guilty over the birthday party that cost their loved one's life.

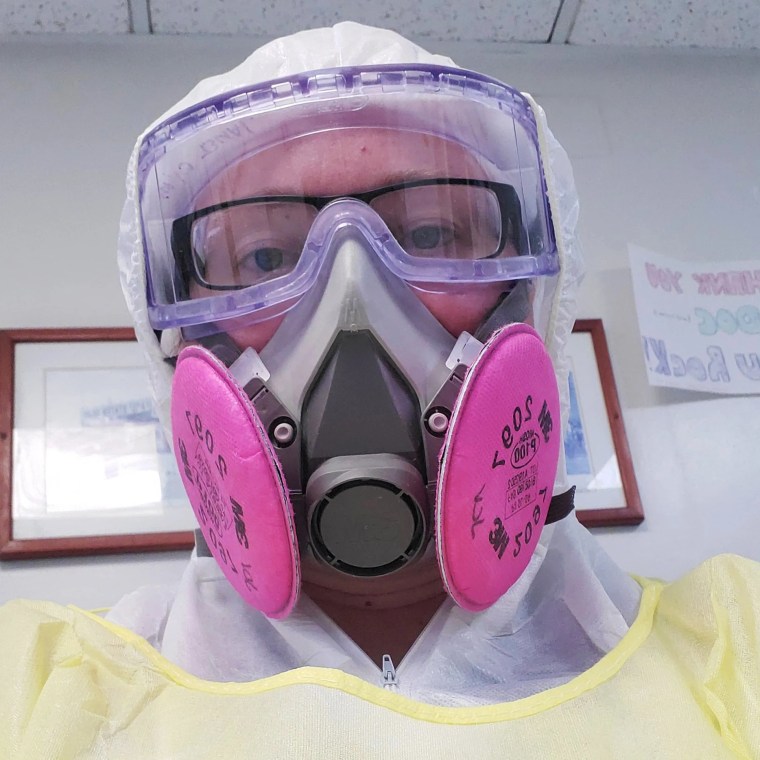

I finally hit my breaking point and recently quit doing direct patient care in a hospital setting. Without sufficient personal protective equipment and staffed hospital beds, a national plan for testing and sufficient relief for those hardest hit by the virus, including hospitals, I didn't have the strength to continue.

A lot of my colleagues are hitting their breaking points, too, and that could lead to a mass exodus from the profession. Americans worry about their local grocery stores' running out of paper towels and toilet paper. Just imagine how much more worried they'll be if their local hospitals, overwhelmed by surges of Covid-19 patients, run out of nurses.

Our leaders have left it up to medical workers to save American lives, but they've denied us the resources to do so. I can't fathom why they're on vacation when there is so much work to do.

Democratic leaders Nancy Pelosi, the House speaker, and Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader, are trying to negotiate a stimulus bill based on the updated HEROES Act that the House passed in October. This legislation would fund a national testing plan to reduce the spread of the coronavirus and increase capacity in hospitals. It would also give states funds for protective equipment and adequate staffing in front-line occupations. But instead of voting on this before the holidays, our lawmakers have left town.

Trump, McConnell and other Republicans must get back to work and meet with the Democrats to pass a coronavirus relief package as soon as possible. They also need to step up their counteroffers to Democrats on what a Covid-19 stimulus package will look like. Until now, Republican counteroffers have been much smaller — more like $500 billion to the Democrats' $2 trillion-or-so proposal — and not nearly enough to deliver meaningful relief for medical workers. Though the major sticking points have been over issues like extra unemployment benefits and relief to the states, there's no question that the so-called skinny GOP approach wouldn't be adequate to meet the needs of hospitals and their staffs.

We need help urgently — to maintain our own health, as well as the rest of the country's. Our leaders seem to have forgotten that medical workers are human beings. Medical workers are contracting Covid-19 from patients, and their sick leave is causing major staffing shortages. And it's causing suffering for those of us enduring it.

My own bout with the virus came in March. I had a fever of 103, followed by a dry cough. I ached all over. The chest and back pain came soon after, followed by fatigue. My muscles burned. Every day it felt like I'd been running a marathon. When I eventually got better, I went right back to work. There was never time for rest.

Many of my colleagues haven't been so lucky, as health care workers are paying the ultimate price for doing their jobs. Those of us who have survived are stretched beyond our capabilities, both emotionally and physically, as we wake up every day to face more tragedy.

In the ICU, I was treating the sickest patients I'd ever seen, under the most difficult conditions. Usually a nurse is responsible for one ICU patient at a time to ensure proper care, but I was pulled in all directions with multiple patients as the hospitals I worked at in New York City and Phoenix exceeded capacity.

I'd be in one patient's room when my other patient's infusions ran dry next door. I'd have to run in before the pump died or the line clotted or their blood pressure crashed. I'd be preparing medications for a patient, and suddenly a group of nurses would have to rush off to assist another acutely ill patient. I would be left to "keep an eye on" all of their critical patients in the meantime.

A lot of my colleagues are hitting their breaking points, too, and that could lead to a mass exodus from the profession.

Now we're back where we started with the virus, except that things are even worse than they were at the beginning of the pandemic, for medical workers and patients. In the beginning, we had a few hot spots, like California and New York, so other states could offer them the critical staff they needed. Now, the entire U.S. is a hot spot, and all the critical staff members are being used; the reserve bench is empty.

Regular people are also simply burned out about hearing about the virus and the need to wear masks and limit exposure, leaving them less likely to help flatten the curve. The result is that the infection, hospitalization and subsequent death rates will grow exponentially. Medical workers like me have done the best we can to keep patients alive. But without support from leaders, our best isn't enough.