The moon landing, which celebrates 50 years this week, was a moment of unity; a moment when the world finally became smaller because we touched a piece of the really big universe. But it was also a moment that we shared together in a way it's hard to fathom in today's world.

When the Apollo 11 spacecraft launched July 16, 1969, it was televised around the country — including in Alaska, which had never received television coverage of a live news event before. It was heading to the moon, for man to set foot on the lunar surface for the first time. The mission was successful as, four days later on July 20, Neil Armstrong did just that. That event was shown globally, from Europe to Australia and Asia to South America. In America, everyone put aside their feelings about seemingly endless war in southeast Asia, a corrupt American president with an enemies list, the hippie leftist progressives who opposed both and sat down to watch television together.

The TV ratings for the Apollo 11 landing are simply unimaginable in this day and age: The 31-hour “TV super-special” peaked with the three-hour moonwalk, which started at 2:12 a.m. on the East Coast. According to historical records, the broadcast had a 93 percent share of households in the United States. In plain English, 93 percent of people watching TV on July 19-20, 1969, saw a man land on the moon. In New York City, the statistic was 100 percent; no one with a television watched anything else. (In 1969, 95 percent of households owned a television; about 95.9 percent of households do today.)

It’s that sense of togetherness that still permeates the story of the Apollo 11 landing today. On the surface, this is the 50th anniversary of a few men blasting out of Earth’s orbit to another heavenly body. But for many, it’s an anniversary of the time that Earthlings watched as the first human officially become a Moonman.

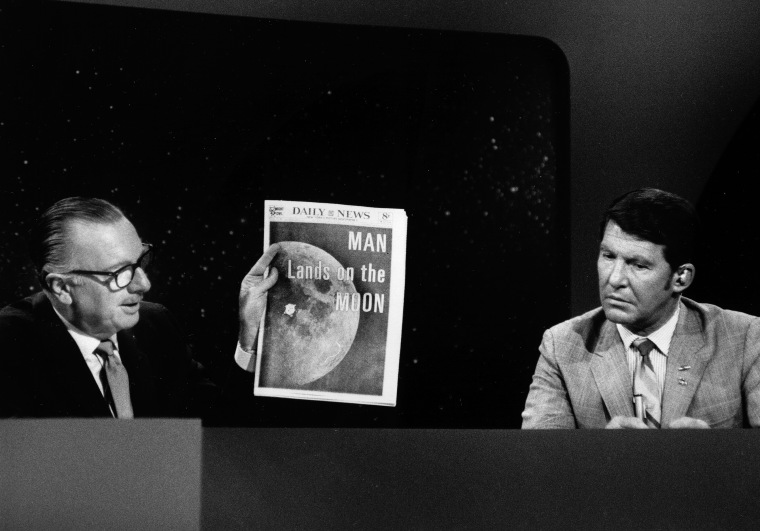

But it is remembered that way because that was how it was packaged. Walter Cronkite — who had an unbelievable 45 percent share of all America audiences — hosted 27 hours of the coverage straight through. He treated the moment with a fever of patriotic wonder, driving home that, in 69 years of the 20th century, the world went from traveling by horse and buggy to traveling in space. It was sold as a worldwide moment, but an America-first one. It’s likely why those who grew up in the Soviet Union are most inclined to believe it was all a hoax, and movies like “First Man” upset conservatives by merely existing.

On the 50th anniversary, it’s not surprising viewers are once again turning back to their televisions to tell them what to think and feel about it. The sheer wealth of footage means there are still brand-new images to see, even 50 years on. But try as television might to unite the entire world in watching a man take a short walk off a ladder, it can’t roll back the clock and get everyone to watch the same thing. Instead, there are a plethora of specials, billing the moon landing as everything from “America’s Greatest Triumph” to cynically exploring how it was sold in the first place.

America’s public television stations led the charge starting as soon as the July Fourth holiday was over with PBS' “Chasing the Moon,” looking at the public relations savvy that went into selling the moonwalk to the public as the ultimate historic event. As far as that special is concerned, the Apollo mission’s success came as much from how NASA sold itself to the public as any scientific breakthrough. The choice to feed reporters like Walter Cronkite with just enough positive news to keep the project going was vital to convincing everyone how much this event mattered.

They followed up this week with a slightly-less-jaded “8 Days: To The Moon & Back" featuring never-before-heard audio recordings from the mission.

Meanwhile, over at CNN, they’ll be airing the TV premiere of the documentary “Apollo 11” which arrived in theaters last March. Initially shot as part of a NASA 1970 documentary, it never aired and sat in cold storage over in the National Archives building for decades before being resurrected by director Todd Douglas Miller.

HBO perhaps has the splashiest of the entries, offering viewers the restored version of the 1998 miniseries “From the Earth to the Moon” about the entirety of the Apollo missions to get to the moon. The 12-part dramatization has a literal who’s-who cast, including Tom Hanks, Tony Goldwyn, Cary Elwes, Bryan Cranston and Adam Baldwin. Though one might think of the 1990s as a cynical time, this series is anything but, as producer Ron Howard, Hanks and Hollywood teamed up with NASA to tell America a story of why it was already great.

HBO may be re-airing Emmy award-winning content, but CBS had Cronkite, and it’s not about to let anyone forget it. The channel is going real-time on its CBSN streaming service, airing each event timed to when it originally happened, from launch to landing. It allows Cronkite’s famous patriotic reactions to paint the portrait of why this anniversary should mean so much.

However, there’s one thing all these TV specials do have in common: They all elide over the question of whether the U.S. will ever go back to the moon. As experts point out, the technology used to send a man to the moon doesn’t even match up to today’s pocket calculators, let alone our smartphones. And yet, the will to get the American public behind the project has failed to materialize every time the agency has tried. The current generation did not live through WWII, barely remembers the Cold War and the “Us vs. Them” mentality of getting there first no longer applies. The ability to promote a unified message via only a few television channels splinters every day as streaming services spread like wildfire.

Television once convinced a generation that going to the moon meant something, and getting there was the biggest achievement of mankind. Until someone figures out how to harness that power again, all dreams of space are merely talk, and moments like the moonwalk will remain consigned to history.