By late May 2008, it was clear that Hillary Clinton couldn't catch Barack Obama and that he would be the Democratic nominee for president.

The calls for Clinton to exit the race were loud, but she ignored them. Asked why she didn't agree with "the party unity argument," she pointed out that "we all remember Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in June in California."

The remark triggered a torrent of condemnation. Kennedy, of course, had been murdered moments after declaring victory in the 1968 California primary, a grisly twist that had the effect of cementing the Democratic nomination for Hubert Humphrey.

Clinton insisted she'd been trying to make a more general point, not to raise the prospect of violence against her opponent. But that she'd reached for the '68 example at all spoke to her predicament. With no realistic mathematical path, her only remaining hope was some kind of extraordinary intervening development — which, of course, proved elusive.

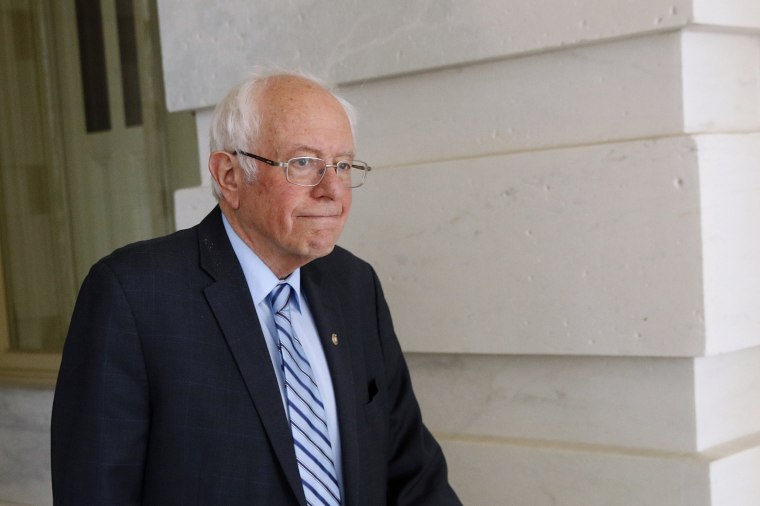

A dozen years later, it's now Bernie Sanders who is facing a grim mathematical reality and suggestions that he close up shop — and who, so far, is staying in the race.

Sanders has lost 11 of the last 12 state contests to Joe Biden and trails in the delegate race by 313, according the NBC News delegate tracker. While he hasn't spoken as bluntly as Clinton did about how he might still win, Sanders has acknowledged that any path for him would be "narrow."

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

In reality, his predicament is even worse than Clinton's was.

The 313-delegate gap is almost four times wider than what Clinton faced in the final weeks of the '08 race. And given the party's proportional delegate allocation system, it wouldn't be nearly enough for Sanders to just start winning primaries.

He'd need to score landslides in giant, delegate-rich states. But it's Biden who's been doing that, winning Florida by 39 percentage points, Virginia by 30, Illinois by 23, North Carolina by 19 and Michigan by 17. Sanders, whose biggest delegate haul came from a comparatively modest 7-point victory in California, has shown no ability to compete with that.

Moreover, it's not even clear that Sanders can win any of the remaining states by even small margins. Take Wisconsin, where he rolled to a 14-point win over Clinton in 2016. A poll has Biden crushing Sanders there, 62 percent to 34 percent. It's the continuation of the pattern seen in just about every primary in March, with Sanders running far below his '16 levels of support in state after state.

Compounding all of this is the changed nature of the Democratic race and of campaign politics in general.

With the coronavirus pandemic upending American life, most states that haven't yet voted have now moved their primaries to June. And while the outbreak certainly qualifies as an extraordinary development, it's not one that has shaken Democratic voters' confidence in Biden in any apparent way. Polls still show him more than 20 points ahead of Sanders nationally. It's an open question whether Democrats will have much appetite for an intraparty battle in the coming months.

And so Sanders is left in need of ... well, something that would utterly reorder the thinking of Democratic voters at a very late date and amid an overwhelming disease outbreak. What could that possibly be? You can try to devise your own scenario. But suffice it to say, he'd be as hard-pressed as Clinton was in 2008 to spell it out in detail.

Otherwise, Sanders is on course to finish out the primary season — whenever it ends — hundreds of delegates and millions of popular votes behind Biden. Maybe that's an acceptable outcome for him. He would still collect many more delegates, thanks to those proportional allocation rules, and would go into the convention — if there is a convention (Biden suggested Sunday that it should be a "virtual" convention") with a large bloc of adherents. Perhaps he would see that as the best way to shape the platform or influence Biden's vice presidential selection.

But there is a risk for Sanders, too.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Four years ago, he was also too far behind in delegates to overtake Clinton and win the nomination. But he continued to run competitively through the end of the primary season, winning states into June. And each victory, or even near-miss, amounted to a show of strength, a reminder that a big chunk of the Democratic Party wasn't sold on Clinton.

But what if, this time around, he sticks it out and there are no more primary wins or even near-misses? What if it's just one landslide defeat after another?

If the late stage of the '16 primary season enhanced his clout, would finishing up now with a string of lopsided losses diminish Sanders and his movement? When he says he's "assessing" his campaign, that may the kind of dilemma he is hinting it.