Florida teacher Amy Spies' classroom is normally so cramped that her 22 fourth-graders do not even have space to hang their backpacks over their chairs.

So if every student returns when school begins next month, there is no way, she says, that her class will be able to follow health guidelines that recommend keeping 6 feet between students to reduce the chance of transmitting the coronavirus.

But Spies' school, R.J. Longstreet Elementary School in Daytona Beach, has yet to present an alternative to her that would make social distancing possible. A move like bringing on a second teacher who could teach half her students in another classroom seems highly unlikely, given her school district's budget is facing a $14 million deficit.

"They have already tried to cut anywhere humanly possible," said Spies, 46, who worries that because she donated a kidney to her aunt in 2011, she would be at risk for complications if she gets COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. "With the safeguards they are attempting to have in place, I just don't know where they're going to get the money, or even the manpower, to ensure it's all happening."

Spies' district is far from alone. As educators across the country look to reopen schools in the fall and welcome at least a portion of their students back in-person, they find themselves in an impossible situation.

With their budgets decimated by the economic downturn, many school districts are wondering how they will pay for costly new cleaning procedures, health screenings and other safety measures for those reentering their schools for the first time since the pandemic shuttered them.

The price tag is expected to be enormous: The average-size district could pay as much as $1.8 million to reopen all of its school buildings under the new safety guidelines, according to a joint analysis by the Association of School Business Officials International and AASA, The School Superintendents Association.

"Districts are looking at significant cuts in their budget and wondering where the money will come from. They're caught between a rock and a hard place, and the biggest fear is they're going to be forced to open schools without the safety guidelines," said Dan Domenech, executive director of AASA, which advocates on behalf of the 14,000 superintendents in the United States.

Still, there is a push to bring students back. Despite no reliable treatment or vaccine yet for the coronavirus, the American Academy of Pediatrics says it "strongly advocates" having children physically present in school, citing some evidence that not only are children less likely to get severely infected by the coronavirus, they also may be less likely to spread the infection.

And remote learning is widely considered to be less effective, with research suggesting low-income, Black and Latino students are experiencing the greatest academic losses.

How, exactly, the fall semester will look will vary across the country: In Florida, Spies' school and others are slated to reopen at full capacity per Gov. Ron DeSantis' recommendations, even as coronavirus cases in the state spike. Florida students can opt to continue remote learning instead of coming back in-person if they have health concerns. Spies has not yet heard how many of her students, if any, will choose that option.

California, which narrowly averted a budget crisis that could have delayed the start of the fall semester in at least six major districts, anticipates a hybrid model combining some face-to-face learning and some remote learning so fewer children will be in the building at one time, making it easier to practice social distancing.

Connecticut will allow students to return in-person but is leaving details up to individual districts. Same with New Jersey, where Gov. Phil Murphy has said it is probable many schools will use the blended model of some learning in school and some at home.

New York City, the nation's largest public school system with 1.1 million students, plans to reopen with social-distancing guidelines, Mayor Bill De Blasio announced on Thursday, although he did not provide details on what that might mean in terms of staggering students' schedules or finding extra spaces to teach them, if the plan proceeds.

“School districts have dealt with economic crises before, but they have not dealt with an economic crisis on top of a global health pandemic at the same time.”

In the meantime, school districts are trimming costs anywhere they can — from not renewing software licenses to deferring maintenance on school facilities to laying off administrative positions in their central district offices, said Elleka Yost, the government affairs and communications manager with the Association of School Business Officials International.

All that still may not be enough.

"The challenges that stand before schools are just Herculean," Yost said. "School districts have dealt with economic crises before, but they have not dealt with an economic crisis on top of a global health pandemic at the same time."

Federal safety guidelines, but not enough federal funding

If schools bring students back in-person, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends they provide adequate soap and hand sanitizer, turn desks to face the same direction, install sneeze guards in areas such as reception desks where it isn't possible to maintain social distancing, provide visual cues like tape on floors to help students and staff stay 6 feet away from each other, and close communal spaces, such as cafeterias and playgrounds, if feasible, or stringently disinfect them between use if not.

The recommendations will be expensive to implement: For an average school district with 3,659 students in 8 school buildings, hand sanitizer alone will be $39,517. Additional custodial staff to sanitize schools could be another $448,000. And if schools add bus aides to screen students for fevers before they board, that would be an additional $384,000.

Congress did provide some funding to schools through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act at the end of March — $13.5 billion — but education advocates say much more is needed.

Hopes were raised this week when Democratic Sens. Patty Murray of Washington and Chuck Schumer of New York on Tuesday introduced a $430 billion coronavirus relief bill for child care and education, $175 billion of which would go to K-12 schools.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, called the bill "visionary" in a statement and said it would "provide the 'must haves' of physical distancing, deep cleaning, PPE for educators and students, and resources to support our most vulnerable students."

Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, urged lawmakers to promptly pass the bill.

“The American economy cannot recover if schools can’t reopen."

"The American economy cannot recover if schools can't reopen, and we cannot properly reopen schools if funding is slashed and students don't have what they need to be safe, learn and succeed," she said in a statement.

But it is not clear when, or if, the bill will pass. An earlier education bill stalled in May, when only the House of Representatives passed the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions, or HEROES Act, a bill that contained about $100 billion for education. The Republican-controlled Senate indicated it won't consider that bill, although last week, Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, said Congress must give schools and colleges the money they need so students can return.

'There are no easy answers'

While all schools are struggling to make their new reality work, experts say districts in which the majority of students live in poverty will be the hardest hit.

Schools are primarily funded through tax revenues, with about 90 to 92 percent of funding coming from state and local sources, including property and sales taxes, Yost said, which have suffered since the pandemic ravaged the economy and cost millions of Americans their jobs. The remaining 8 to 10 percent of funding is generally federal.

In Cobb County, Georgia, which has about 113,000 students, school officials are looking at a $65 million shortfall, according to John Floresta, the school district's chief strategy and accountability officer. That's after the county received approximately $16 million in federal funds from the CARES Act.

"We appreciate that," Floresta said of the CARES funding. "But in a district with a $1.2 billion budget, it doesn't amount to much."

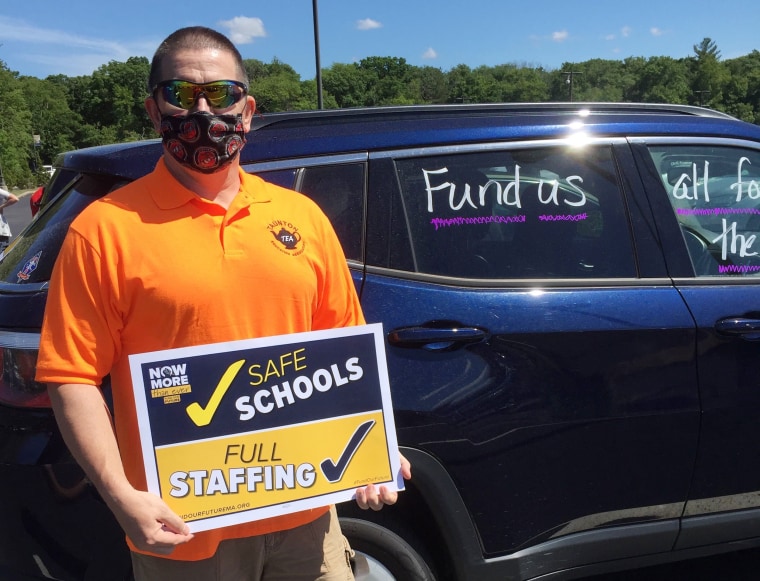

Meanwhile, in Taunton, Massachusetts, about 160 teachers and staff have received layoff notices ahead of the new school year amid a $5.8 million budget cut for the district.

James Quaintance, a career technology education teacher at Taunton High School and president of the Taunton Education Association, said if students return to class in-person, they will require more teachers, not fewer, and more money to fund a safe education.

"It's unconscionable that people would expect us to provide a quality education to the students in this environment," he said. "You're going to have to do more with less. It's simply crazy."

Spies, the Florida fourth-grade teacher, is unsure how her school year will look. Her Title 1 school, where about 75 percent of students receive free or reduced breakfast and lunch, does a lot on a shoestring budget to begin with.

Even before the coronavirus hit, Spies and other teachers had complained that the custodial services, which the district outsourced years ago, did not provide a satisfactory level of cleanliness. School buses were already crowded.

If the funds aren’t there, how are we going to make it happen?”

Now, there is even less to work with. Her district has just eliminated its social-emotional learning department as a cost-cutting measure, removing services Spies feels her students will need more than ever when they return.

"This has been the most challenging time of my educational career," Spies, who has taught for 23 years and was named her school's most recent Teacher of the Year, said. "Lying awake nightly trying to think what we can do to best protect our students and also trying to ensure that the opportunity gap doesn't become even larger just weighs so heavily."

"There are no easy answers," she added. "If the funds aren't there, how are we going to make it happen?"