This article was published in partnership with the Houston Chronicle.

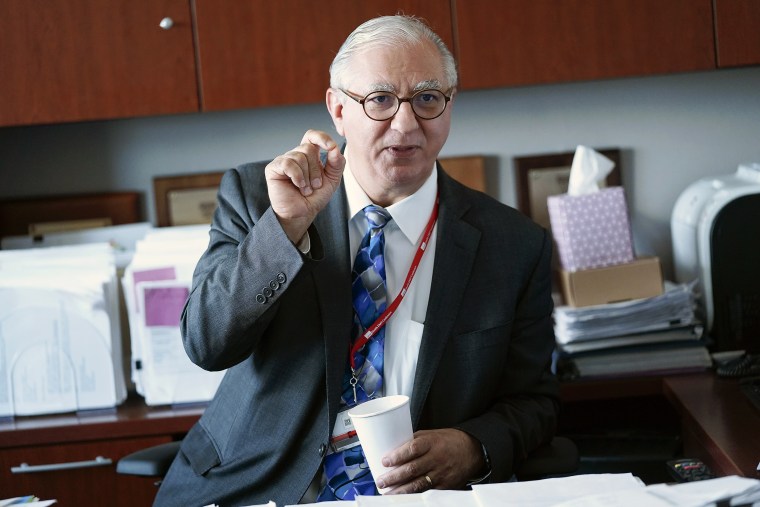

GALVESTON, Texas — Dr. Michael Laposata noticed a disturbing pattern two decades ago, when he was the director of clinical laboratories at Massachusetts General Hospital and a Harvard Medical School professor.

The state was taking children from their parents based on mistakes by doctors. Children with bruises or internal bleeding were being misidentified as victims of abuse after doctors missed underlying medical conditions that can cause those same injuries.

Physicians are human, Laposata said, and mistakes are bound to happen. But he said it's hard to imagine a worse misdiagnosis than that of child abuse.

"When we get this one wrong," he said, "you take a kid away from a loving family, and a caretaker goes to jail."

In the years since then, Laposata says he’s reviewed hundreds of cases on behalf of accused parents and helped overturn several convictions. Now the chief of pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, he is part of a growing cadre of physicians who, along with lawmakers, are advocating for stronger safeguards to prevent child abuse misdiagnoses following a yearlong investigation by NBC News and the Houston Chronicle.

Texas lawmakers have launched a series of hearings in response to the reporting, and some have proposed enabling courts or parents to seek a second medical opinion after a doctor reports abuse. Other lawmakers have suggested changing the way Child Protective Services approaches investigations when the only evidence of abuse comes in the form of a doctor’s note. Lawmakers said they plan to take up these proposals in the state’s next legislative session in 2021.

Mike Schneider, a former juvenile court judge who imposed a record $127,000 sanction on the Texas child welfare agency for its mishandling of one of the cases highlighted by NBC News and the Chronicle, agrees that additional medical opinions would be helpful. He said that usually the only doctors who testify in child welfare cases are the ones who reported the abuse.

But the state would likely reach the right conclusion more often if the system made it easier for accused parents to request second opinions, he said.

“Why wouldn’t it make sense to have everyone have access to the same sort of expertise?” Schneider said. “The whole point is to get to the truth.”

Nationally, almost 1,700 children died from abuse or neglect in 2017, according to the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. To help prevent these deaths, children’s hospitals employ pediatric specialists who are trained to differentiate accidental injuries from those that have been inflicted.

By law, all doctors are required to notify authorities when they suspect a child may have been abused. Child abuse pediatricians go further: They then examine a complete picture of the child’s injuries and try to confirm whether abuse has occurred, diagnosing not only a child’s medical condition, but also what caused it.

In Texas and in several other states, the work of these doctors is funded in part by grants from the state’s child welfare and public health agencies, which deputize the hospital-based medical teams to review cases on behalf of Child Protective Services. Their work is particularly vital in cases involving children too young to describe what happened to them.

But in their zeal to protect children, some child abuse pediatricians also have implicated parents who appear to have credible claims of innocence, leading to traumatic family separations and questionable criminal charges, the NBC News and the Chronicle investigation found. In some cases reviewed by reporters, treating physicians or other medical experts disagreed with the conclusions of state-backed child abuse pediatricians, but Child Protective Services did not take those doctors’ opinions into consideration before separating families.

The state took Ann Marie Timmerman’s 4-month-old son in 2016 after he suffered a seizure and a child abuse pediatrician diagnosed him as a victim of shaken baby syndrome. A pediatric neurosurgeon at the same hospital told the family that the seizure was caused by an underlying medical condition, but the state did not consult that doctor, and it took Timmerman and her husband seven months to prove their innocence and regain full custody.

"Had the state not completely disregarded the initial treating neurosurgeon's diagnosis, we wouldn't have had to endure the unnecessary trauma caused to our family," Timmerman said. “Second opinions in cases like mine should be automatic.”

Dr. Tammy Camp, the president of the Texas Pediatric Society, said in a statement that the reporting demonstrated just how difficult it can be for doctors to determine whether a child’s injuries were inflicted. That’s why child abuse pediatricians spend years training to identify conditions that can be confused for abuse, she said.

But even then, she said, “the diagnosis of abuse usually is not black and white, but rather a prediction of risk.” She pointed to instances in Texas in which child abuse pediatricians were not consulted, and children died.

“The current system is a vast improvement over the protections that were in place 20 years ago, before the availability of child abuse pediatric consultations,” Camp said, “but enhancements can always be made.”

The Texas Pediatric Society has begun discussing ways to improve the system, Camp said, but she stressed that any changes “must be carefully evaluated for potential unintended consequences to the health and safety of these most vulnerable children.”

Before any adjustments are made, Laposata said doctors and government officials must acknowledge what is widely known across all fields of medicine: Even good doctors make mistakes. Such errors are so common, researchers estimate that 12 million Americans receive a misdiagnosis every year, sometimes with devastating consequences.

For that reason, Laposata believes that additional medical experts should be consulted at the start of these cases rather than after an abuse diagnosis has already been made.

“It’s so crucial that we get this right at the beginning and not after a child has been wrongly taken from parents, or worse, sent back into a home where he’s being abused,” he said.

Laposata is advocating for a model he piloted a few years ago, when he moved to Texas and assembled a multidisciplinary team to provide free case reviews for parents who believe they’ve been wrongly accused.

Each month, the team examines about a half dozen abuse cases from across the country, looking for mistakes or missed medical problems that might explain a child’s injuries. The team then meets to discuss each case and attempts to reach a consensus. Sometimes they agree with the doctors who initially reported abuse, Laposata said, but other times they uncover exonerating evidence.

Similar panels could be set up to review cases on behalf of the state, either funded by the government or independently, Laposata said. Ideally they would include not just pediatricians, but also pediatric subspecialists and pathologists with experience diagnosing a wider range of conditions that could mimic abusive injuries.

Including additional physicians could also reduce the risk of errors resulting from the bias of an individual doctor, which is a leading cause of medical mistakes, Laposata said.

“I think the biggest problem in these cases is that other experts are often not asked to weigh in,” he said. “Maybe you’re a pediatrician and you’ve been named to the child abuse group, but you never spent time in coagulation with a child who’s bruised or bleeding. Or in orthopedics or endocrinology with a child with broken bones. Or in dermatology with a child who has skin changes. Experts from all of these disciplines need to be consulted.”

That sentiment was repeated in more than a dozen messages from pediatric subspecialists who contacted NBC News and Chronicle reporters in recent weeks with stories of patients who they said were diagnosed as victims of abuse by a hospital child abuse team despite what they believed was evidence to the contrary.

Dr. Gary Brock, a pediatric orthopedist who’s been working at the Texas Medical Center in Houston for 29 years, said he’s seen doctors report children with broken bones as confirmed victims of abuse despite strong evidence, in his opinion, that the injuries were not inflicted.

“There’s very few injuries we can look at and say, ‘That’s definitely child abuse,’” Brock said. “So for a pediatrician to say that, who has little training in radiology or in orthopedics, it should be mandatory that they have a second opinion from a specialist.”

Brock suggested finding a way to make it easier for treating physicians with busy clinical schedules to testify in court, potentially through conference calls.

“I would really stress that everybody wants to get it right, and the safety of the child is absolutely foremost,” Brock said. “But in circumstances where at least half the time we can’t tell the difference between accidental trauma and non-accidental trauma, multiple opinions are mandatory, not optional.”