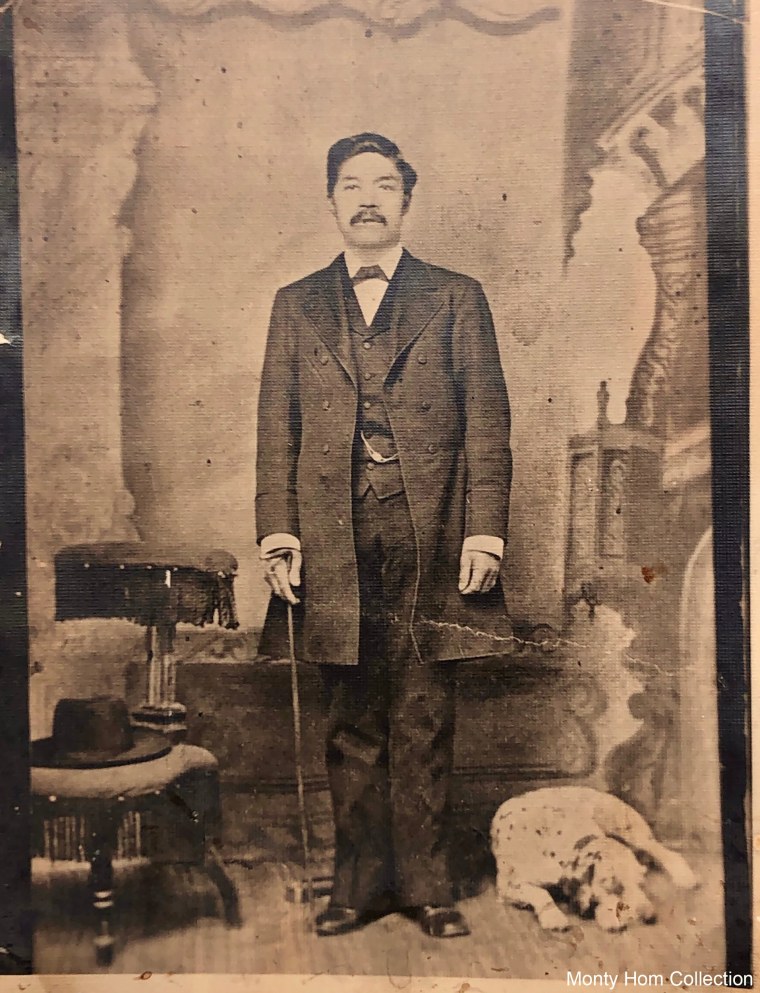

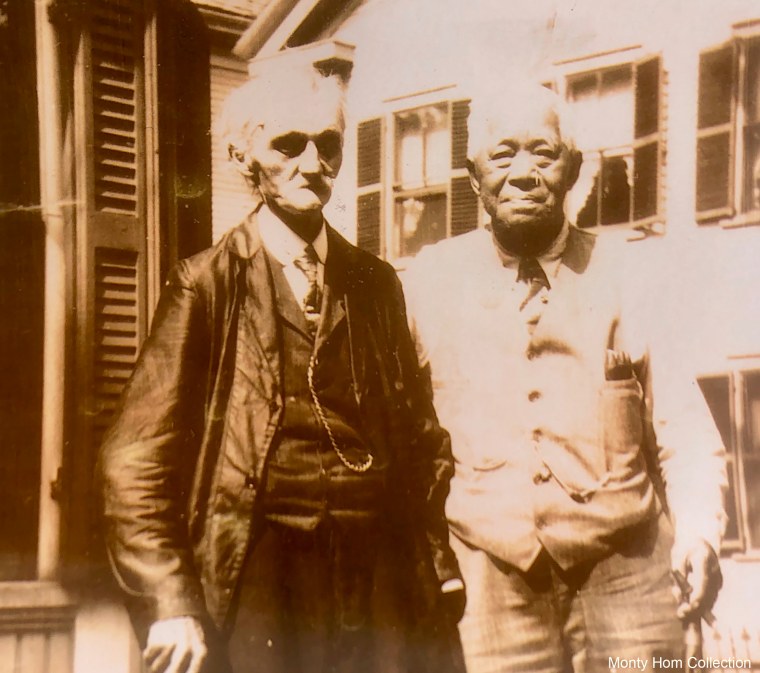

Edward Day Cohota believed he was an American citizen, even when his adopted country told him otherwise.

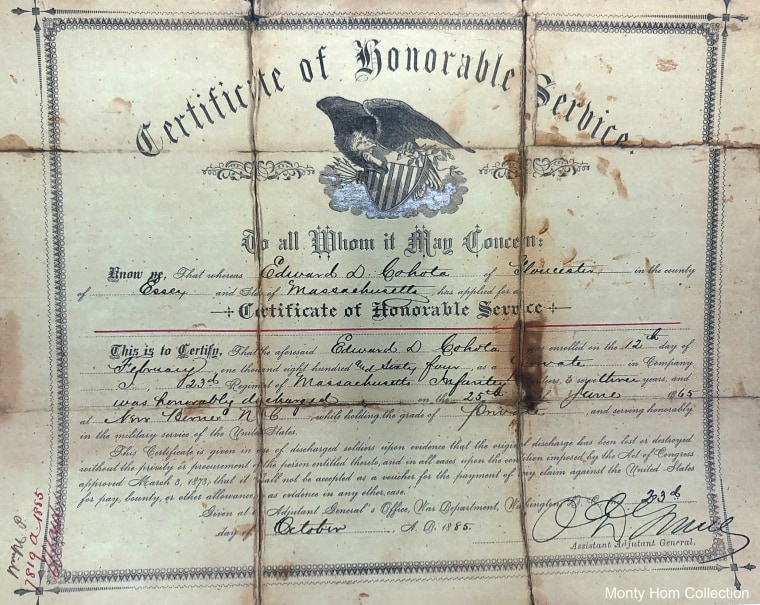

A Civil War veteran who fought for the Union, Cohota saw combat in significant battles in Virginia. He went on to serve 30 years in the Army, married and had six kids, and settled down in the Midwest to start a business.

Cohota was unlike most Civil War veterans: He was Chinese, adopted by a merchant ship captain who discovered the half-starved boy (and another who later died) aboard his boat named the “Cohota” after it left Shanghai. He arrived in the United States in the 1850s.

“He was a highly patriotic individual who raised and lowered a flag in front of his house every day,” said Montgomery Hom, a filmmaker who researched Cohota’s story for a documentary in post-production entitled “Men Without a Country: Chinese in the American Civil War.”

Amid rising anti-Chinese sentiment, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which prohibited most Chinese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens.

Before its passage, Cohota had failed to submit his second set of naturalization papers. He died in 1935, following an unsuccessful decadeslong battle for citizenship.

“That’s kind of the greatest tragedy,” Hom said. “He did all this for his country, but his country didn’t recognize him.”

Since the Civil War, generations of Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians have gone on to serve and distinguish themselves in the U.S. military. That includes the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Coast Guard and National Guard.

Some have paid the ultimate sacrifice with their lives; some have barely survived saving others. While fighting the enemy, they also fought discrimination at home, from those who viewed them as less than American. Sometimes that included their fellow troops.

From the Philippine-American War to the Vietnam War, close to three dozen Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration for valor, according to Daniel P. McDonald, director of research and development at the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute, part of the Department of Defense.

Over the last decade, Japanese, Filipino and, most recently, Chinese American veterans who served during World War II have also had their contributions recognized with a Congressional Gold Medal for each group — an honor that advocates say was long overdue.

“It was good satisfaction in seeing that the award was made,” said retired Maj. Gen. William S. Chen, the Army’s first two-star Chinese American general who helped lobby for the medal for Chinese American veterans.

Pre-World War II

Research published by the National Park Service shows that Asians and Pacific Islanders were among those who fought in the Civil War. That includes men from India, Japan, the Philippines, Guam and China.

Hom estimates that between 50 and 100 Chinese had enlisted, primarily in the Navy. He added that there were less than 1,000 Chinese living on the East Coast during the Civil War. The majority of Chinese fought for the Union, though a few joined the South.

Some came by way of the Caribbean and Cuba, where they were indentured or contracted laborers. Others like Cohota, were picked up and adopted by American sea captains who worked aboard ships in Asian waters, Hom said.

Later on, at the turn of the century, Filipinos found themselves called into action after Spain ceded sovereignty over the Philippines to the U.S., following the Spanish-American War of 1898.

After Filipinos declared the Philippines an independent and sovereign nation — a declaration the U.S. did not recognize — clashes erupted between independence-seeking nationalists and U.S. forces in the islands.

The U.S. established a civil government in the Philippines, and in 1901 Filipino soldiers who had fought for the U.S. against the nationalists were incorporated into the Army as the Philippine Scouts, an outfit whose heroism and bravery would be vital to winning World War II.

In addition to smaller conflicts, Asians also served in World War I. Among them was Bhagat Singh Thind, a Sikh U.S. Army veteran who, after returning home, saw his citizenship revoked following changes to U.S. law.

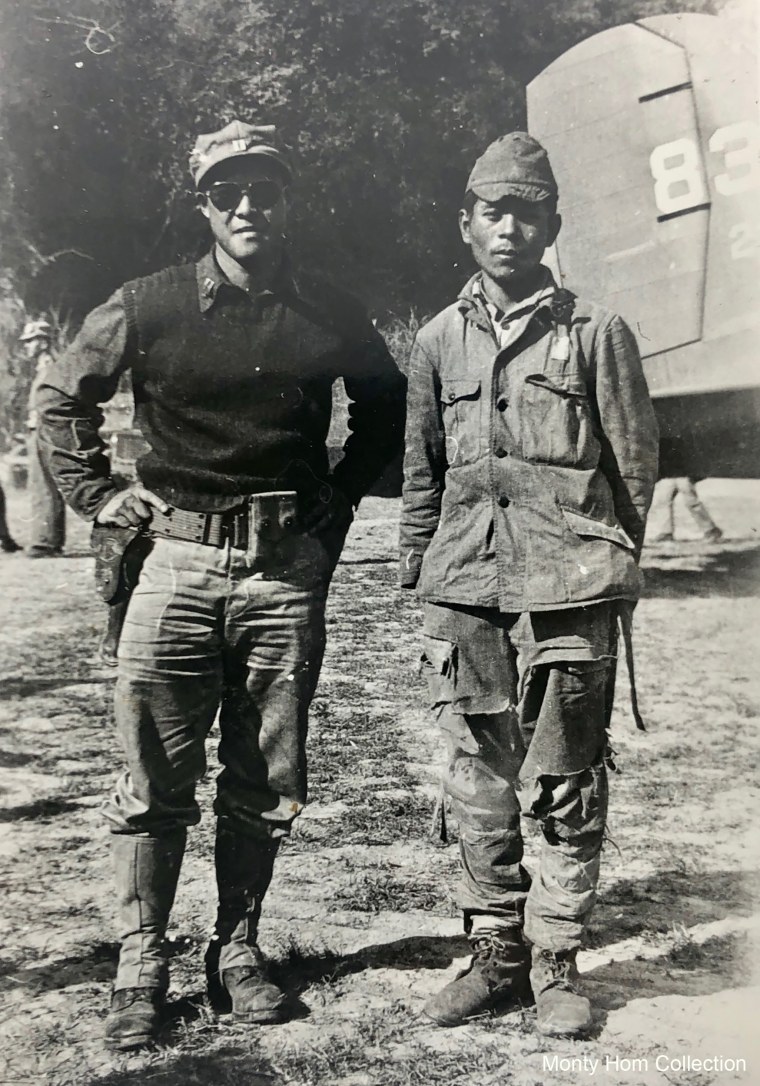

World War II

Japan’s surprise air attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, brought the U.S. into World War II.

A little more than two months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which set in motion the rounding up of more than 120,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent to be sent to incarceration camps in the interest of national security.

Despite this, Japanese Americans stepped up to fight for their country. Around 19,000 served in the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service.

Terry Shima, 96, was one of them. He was born in Hawaii and spared detention in an incarceration camp. Because Japanese Americans were crucial to Hawaii’s economy, the FBI there detained only leaders of the Japanese, German and Italian American communities after Pearl Harbor.

In 1944, Shima was drafted into the 442nd, a segregated Army unit comprised almost entirely of Americans of Japanese ancestry. (The late Col. Young Oak Kim, a Korean American and winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second highest award, joined as a second lieutenant.) The 442nd was the most decorated unit in military history for its size and length of service.

Unlike the Japanese Americans, the Chinese Americans were integrated into the U.S. military.

Hom, who directed the 2000 documentary “We Served with Pride: The Chinese American Experience in WWII,” said upwards of 20,000 Chinese Americans fought in World War II. Around 40 percent were not citizens.

Their service overlapped with the period during which the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect. (It was repealed in 1943.) Hom said joining the military allowed foreign-born Chinese to gain citizenship.

“One of the impetuses of why they did their service was they all wanted to be in this country, because it was a land of opportunity,” he explained.

For Filipinos, the call for all organized military forces of the former American colony came from Roosevelt on July 26, 1941, less than five months before Japan attacked the Philippines and also Pearl Harbor.

Between 1934 and 1946, the year the Philippines gained independence, the U.S. maintained the right to summon Filipinos to serve under the U.S. Armed Forces.

Among the outfits were the Philippine Commonwealth Army; the Philippine Scouts, established in 1901 during the early days of American occupation; and recognized guerrilla units, which helped provide intelligence to Allied forces to repel the Japanese.

More than 260,000 Filipino and Filipino American soldiers served during World War II. Despite their service, these veterans, who were U.S nationals, were disqualified from receiving the same rights, benefits and privileges as others who served under the U.S. Armed Forces, the result of the Rescissions Act of 1946.

“If you fight for your country, the least you could do is recognize them,” said Army retired Maj. Gen. Antonio Mario Taguba, who lobbied for a Congressional Gold Medal for the Filipino and Filipino American World War II veterans.

Former President Barack Obama signed a law in 2009 creating a fund granting $15,000 to Filipino vets who are U.S. citizens and $9,000 to those who are not. Both are one-time payments.

Post-World War II

The service of Asians, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians before and during World War II paved the way for future generations of men and women to join what in 1948 would become a desegregated U.S. military.

The Korean War, Vietnam War and Iraq War were among some of the conflicts during which Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians have served. Others like Hmongs and Laotians fought alongside the U.S. during a “secret war” in Laos against North Vietnamese forces. Those who did and came to the U.S. as refugees were provided an expedited pathway to citizenship through naturalization.

Vietnamese who were evacuated as refugees to the U.S. during the Vietnam War have also joined the armed services. Army Maj. Gen. Viet Xuan Luong became the military’s first Vietnamese-born general in 2014, when he was promoted to brigadier general.

Congress, for its part, also counts Asian American and Pacific Islander veterans among its ranks.

That includes Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, who served two tours of combat duty in the Middle East, and Sen. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., a Black Hawk helicopter pilot who was shot down during Operation Iraqi Freedom and lost her legs.

Today, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians account for 5.6 percent of active duty military personnel, Department of Defense figures show. Nationwide, these three groups make up 6 percent of the population.

“That’s a good proportion,” Taguba said of the percentage in the military. “But what’s more important is that they continue to serve, as opposed to just being a data point.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.