He was one of the world's most famous figures, but Neil Armstrong famously shied away from the spotlight. After becoming the first person to step foot on the moon, on July 29, 1969, the NASA astronaut returned to his Ohio roots and led a low-key life as a college professor.

Not many people know much about the man behind the mission. But one who does is James Hansen, a history professor at Auburn University in Alabama and Armstrong's official biographer. His 2005 book, "First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong," is the basis of the new movie "First Man," starring Ryan Gosling as the legendary moonwalker.

In Gosling's portrayal, Armstrong is relentlessly focused on the task at hand and unfazed by the danger he faces as a test pilot and astronaut. Was Armstrong, who died in 2012, really that coolheaded in real life? How was he affected by his young daughter's tragic death? And what sort of relationship did Armstrong have with his Apollo 11 crewmate Buzz Aldrin?

To get the full picture, NBC News MACH sat down with Hansen on the Auburn campus to discuss Armstrong's storied life and career.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

MACH: How did you get involved with Armstrong, and how did you get his cooperation for your book?

Hansen: Neil was a very private man, and it wasn't easy to get his permission to do the book. I think the keys were that I was about 20 years into my career when I approached him, and I had been writing and teaching about aerospace history, both aeronautics history and space history. When I approached him I had a body of books and articles that I could show him. All of my books prior to approaching Armstrong had really dealt a lot with the history of engineering and how engineers think. I think Neil knew that I would take his technical side seriously. A lot of authors who had approached him before didn't have that kind of background, so I think that was really essential.

The movie opens with Armstrong taking an X-15 rocket plane to the edge of space. Was there something in his childhood that put him on a path to become a test pilot and then an astronaut?

I'm a strong believer that you don't understand any adult unless you understand their childhood. The biography that I wrote deals a lot with him as a boy and as an adolescent. Certainly, from an early age he was passionate about flying. He started nagging his mother when they visited dime stores in these little Ohio towns that the family lived in to get little balsa wood airplane models that he would build, and then he advanced to gasoline-powered models.

He would train his little brother and sister to toss them out the upstairs window of the house in just a certain way so they would glide the best. Neil would be outside — he would have Popsicle sticks, and he would put the Popsicle stick in the ground where that particular model airplane had landed. Even as a 10-year-old he's essentially doing test flying. He's doing research. He's studying. He had a little notebook as to how far each one of the models flew. He was kind of a proto-engineer even as a boy. Then, of course, he got his pilot's license on his sixteenth birthday. He hadn't even started to drive, or even try to drive an automobile. He was already flying airplanes.

Was he a reluctant hero?

There was nothing in Neil's personality that really tried to find the limelight. After Apollo 11 he didn't like the celebrity that went with it. Of course, he had become a global icon, the first of our species to step on another heavenly body. It was never about fame or fortune for him. It was about the flying. The most important thing to him about Apollo 11 was, "Let's fly this lander down to the successful landing and not kill ourselves." The act of stepping out onto the lunar surface was, for him, almost an afterthought and very secondary.

Later he did everything he could to try to lead a normal life. It was kind of hard to do that once you had become first man. For a while after Apollo 11 he was getting 10,000 fan mail letters a day that he did his best, with some help from NASA secretaries, to answer. To the end of his life he was getting requests for signatures and photographs and appearances at all kinds of events. He went to many of them, so he wasn't really reclusive. He had to be kind of selective about what he agreed to do.

Was he really as aloof as Gosling portrays him in the movie?

The movie does a good job of depicting Neil because Ryan Gosling did such a great job of portraying him. When an actor in a movie is playing a historical character, the best you can hope for is a really solidly researched role, and Ryan did that. Ryan not only read my book very carefully and had many conversations with me, but he had conversations with Neil's two sons and with Neil's sister and lots of people that knew him. As Ryan told me, he wasn't trying to mimic Neil. He wasn't trying to become Neil. He was trying to interpret some truths about Neil's character. I think he did that very well. Neil's two sons, Mark and Rick Armstrong, who are now grown up, both feel that Ryan's portrayal of Neil was the father — the man — they knew.

How did Armstrong and Aldrin come to be picked for Apollo 11?

It actually is just a matter of how the rotations of crews were put together and how the missions worked out. If Apollo 8, 9 and 10 had not worked out as well as they did, then the missions would have slipped and Apollo 12 could have been the first landing, with Pete Conrad as the commander.

Deke Slayton was the head of the Astronaut Office, who put the crews together, and he felt that the key thing was to pick six or seven really good commanding astronauts, and then put the crews together under those commanders. It wasn't as if Neil was from the beginning ordained to be the landing commander. It just really turned out to be that his crew was in the right place at the right time.

What kind of relationship did Neil and Buzz have?

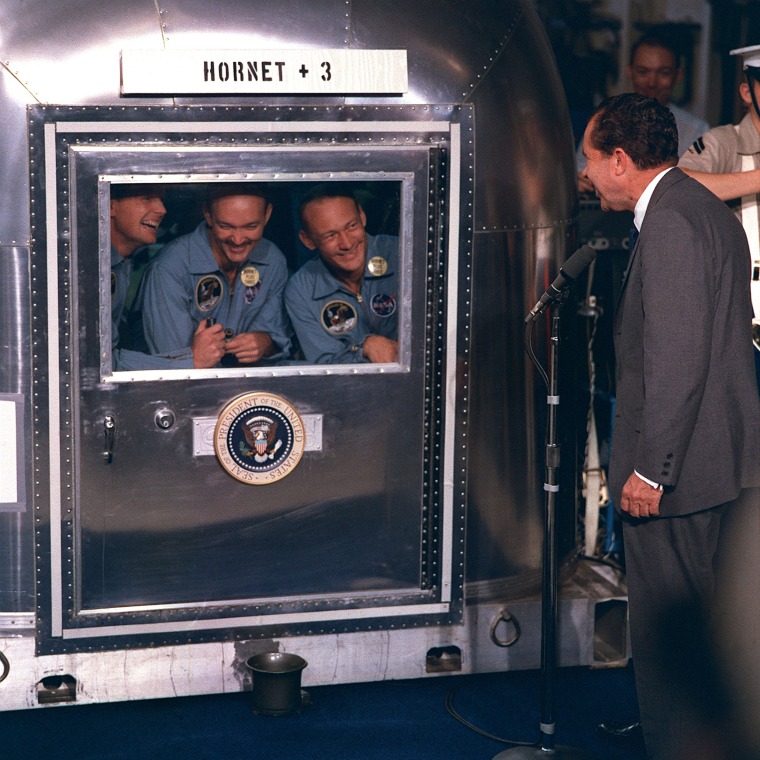

Mike Collins, the third member of the crew, I think put it the best. He has described the Apollo 11 crew as amiable strangers. In other words, they were friendly enough, but they kind of remained strangers to one another. They did their job, they did what they had to do professionally, but when it was lunch or the end of the day they didn't go out together and drink a beer. They just sort of went their separate ways.

I said to Mike Collins, in my interview with him: "Well, what about just Neil and Buzz, just the two of them?" Mike was very thoughtful, and had a really good sense of humor and good insight into people. Mike thought for a minute and said: "Neutral strangers." He didn't even include the amiable part.

Armstrong's two-year-old daughter, Karen, died of a brain tumor in 1962. How did that affect him?

I knew it was going to be a very private subject because there were people that knew Neil well in the succeeding years that didn't even know that Neil had a daughter, because he never talked about it. In my interviews with his wife, Janet Armstrong, I discovered he didn't talk about it with her either. I got Neil to talk about it, probably more than anybody else ever had, but I also talked to Janet about it. I talked to Neil's sister, June, about it. June really understood her brother. She told me that Neil just loved that little girl so much, and that he really never got over it.

I wanted to see what the effects might have been on him. I looked at his flying — he was still a test pilot at the time she died. I looked at his flying record over the next few months before he became an astronaut, and there was a series of troubled flights, problems that occurred in different flights that had never happened, really, in his flying career before. I really was examining whether the emotional impact of the death of the daughter, whether it affected his flying. Then, ultimately, did it affect his decision to become an astronaut? I really concluded that it did play a role.

Iin his classic way of talking about things, or avoiding talking too much about things, when I asked him about the effects of the death of his daughter on him and his career — and this is a line we built directly into the movie — Neil answered me: "Well, I think it would be unreasonable to assume that it would have no effect." It wasn't very elaborate, but he admitted that something like that has to have an effect.

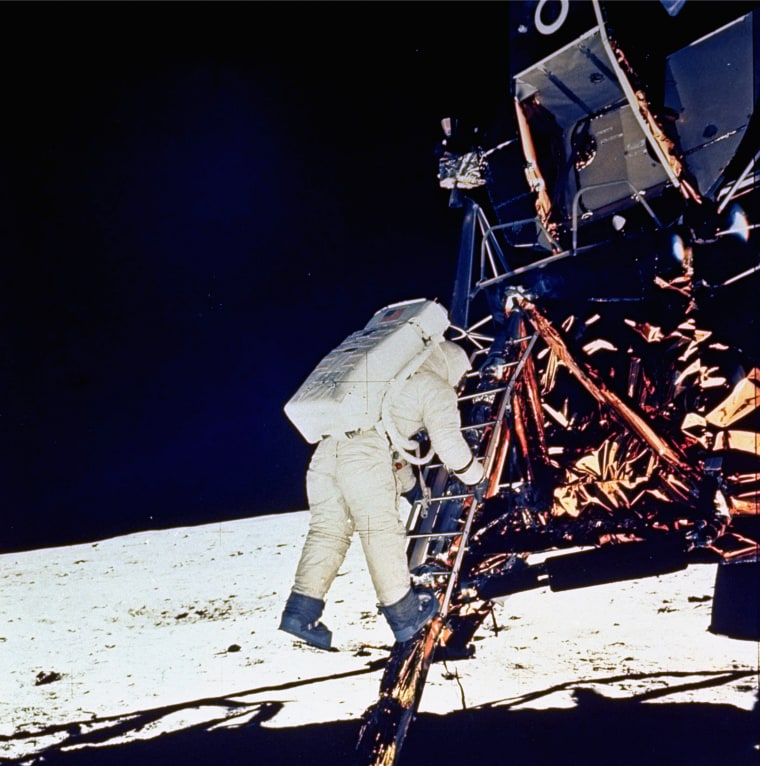

Near the end of the movie, Armstrong drops his daughter’s bracelet into a lunar crater. Did that really happen?

That's a little bit of dramatic license, because we're really not sure what, if anything, he did like that. We don't know what he took to the moon with him personally. Each of the astronauts had what was called a personal property kit, a PPK. In the PPK, which was like a little pouch, they could put things like rings, jewelry, badges, different kinds of things that maybe they were taking for themselves or taking for other people. Each astronaut made a record, wrote down what they put in their PPK before they left the flight. It was kind of a manifest of the contents. Well, Neil's manifest for his PPK has never been seen. I asked to look at it during my time with him for my interviews, and he said he would find it and show it to me, but that never happened. So we're not really sure what all he took.

Another part of the mystery is the trip he made over to Little West crater, where in the movie he leaves the bracelet. That was not a scheduled visit. It was not scripted in the mission plan for him to even go over there. He didn't have a lot of time to get over there because the men in mission control were already telling Aldrin and Neil to get back in the [Lunar Module], that they had been out long enough and it was time to go back. Neil rushed over, got quite exerted. His heart rate went up to over 180. The TV camera that was on the lunar module wasn't pointing at him, so we don't know exactly what he did over there.

It's a poignant moment in the film, and I guess I just leave it with the following thought: that there are times when the power of poetry prevails over the uncertainty of fact.

Want more stories about human spaceflight?

- Why astronaut Chris Hadfield isn't afraid of death

- The human factor: What it will take to build the perfect team for traveling to Mars

- New moon lander would be a big step up from Apollo-era 'modules'