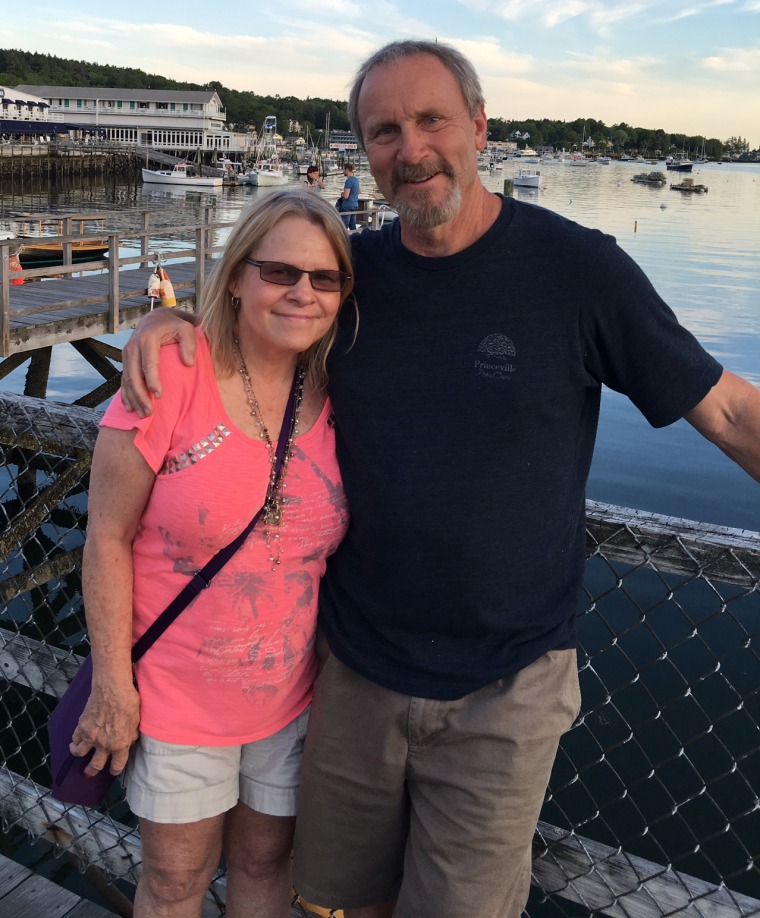

For more than 30 years, Dean Dennis and his wife, Patty, worked in the Cincinnati school system, paying into their pensions so they wouldn't have to worry about retirement. "We managed our money well. We had our plans for our future," Dennis said.

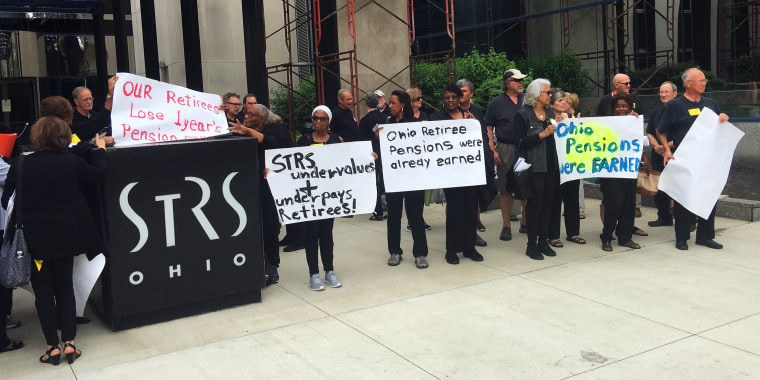

But the Dennis family's plans and those of thousands of other former educators and school system workers in Ohio have been upended. In 2017, the State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio, or STRS, pension plan eliminated an annual cost-of-living increase. Since then, recipients have had no increase in payments while prices have risen by 8 percent.

Dennis sued the pension plan after the cost-of-living adjustment was eliminated, a case that is pending in federal court. Now, he says, he is concerned about the safety of the $88 billion fund after an analysis concluded that its overseers are overstating performance through a misleading benchmark and doling out undisclosed fees to Wall Street private equity and hedge fund firms.

Some of the fees likely to have been paid to the financial firms would more than cover the cost-of-living increase that was eliminated, the report said.

The analysis, commissioned by the Ohio Retired Teachers Association, an advocacy group, and released Monday, says the fund's holdings are opaque and carry high fees on actively managed portfolios — some estimated at 2 percent, far more than the low-cost market index funds that are run by companies like Vanguard and Fidelity, which millions of U.S. consumers use without a money manager's advice.

A newly elected member of the pension plan's board said relying on active managers may have cost the fund $4.1 billion in the past decade.

More than 500,000 beneficiaries rely on the STRS pension fund, 157,000 of them retirees. Ohio teachers contribute 14 percent of their salaries to the fund each year, an amount matched by their employers. Members aren't eligible for Social Security. Last year, the average retiree received $44,000 in annual pension payments, according to the fund's annual report.

Overall, the Ohio pension had a net one-year return of 3 percent last year, just under the 3.3 percent of the median pension, according to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators. Over three years, it generated 6.44 percent, versus the median fund's returns of 5.8 percent and 6.8 percent for five years, compared with the median gain of 6 percent during that period.

Like many other pensions, the STRS plan is underfunded — with about 77 percent of its liabilities covered, records show. Underfunding was the reason managers gave when they did away with the 2 percent cost-of-living increases four years ago. The largest 100 public pension plans were about 71 percent funded as of December, according to an estimate from Milliman Inc., a risk management and benefits firm.

Nick Treneff, a spokesman for the Ohio pension plan, said in a phone interview that fund overseers take issue with some of the new report's assertions. Private equity and hedge funds have added to the fund's performance over the past 10 years, he said. He also rejected the report's criticism of high fees, saying the fund's costs are on "the reasonable to low side" compared to those of peers.

But the fees he is referring to — $303 million, or 0.40 percent of assets in 2018 — don't include transaction costs and performance fees associated with private investments, which is why some beneficiaries are asking for more information.

"This is something that we take very seriously," Treneff said. "We are hoping to build a stable system, strengthen the fund and improve sustainability for everyone in the fund."

'Confidentiality agreements'

The Ohio fund, like most public pension plans, invests in stocks, bonds, real estate and an array of high-cost hedge funds and private equity portfolios. But its bets in the last two areas are larger than those of some of its peers, accounting for over 18 percent of the fund's portfolio, the pension plan's annual report shows. Its private equity holding is 10.6 percent; by comparison, the California Public Employees' Retirement System, or CalPERS, the country's largest public pension fund, with over $450 billion in assets, reported a 7.7 percent allocation to private equity.

The Ohio pension plan's holdings in private equity and hedge funds have stumbled. In each of the past five years, the investments returned an average of 6.7 percent, well below the almost 10 percent goal the report cited. They lost 1 percent in fiscal year 2020, the fund's annual report ending June 30 shows; by this spring, the performance had rebounded, according to unaudited figures.

The Ohio fund invests with about 140 money managers. Apollo Global Management and the Carlyle Group, both giant private equity firms, are two of them.

In a statement, an Apollo official said that the firm's performance has been strong and that it is transparent. "Apollo's investors receive regular, detailed reporting of all fees, expenses and carried interest they pay in our funds," the official said.

A Carlyle spokeswoman said, "For more than 30 years, Carlyle has delivered strong returns across asset classes and geographies, helping provide retirement security for public and corporate-sector employees including teachers, police officers and firefighters."

Private equity firms buy companies, borrowing money to do so, and hope to sell them at a profit later. The investments are opaque and high-cost, critics say. Regulators have identified private equity's costs as a problem for investors; in 2014, after examining 150 private equity firms, the Securities and Exchange Commission found that more than half had violated the law or were deficient in their handling of fees or expenses.

Nevertheless, in recent years, pension funds have invested large amounts in such strategies to boost their returns. Supporters of private equity say its returns beat those of other strategies.

While past returns may have been superior in the early 2000s, outperformance appears to be dwindling more recently. Last year, Ludovic Phalippou, a professor of financial economics at the University of Oxford's Saïd Business School, published a working paper that found that private equity returns since 2006 have roughly equaled those in public stock indices. Index investing is far cheaper than private equity, and Phalippou noted in his research that hundreds of billions in fees paid by private equity investors have gone to a small number of people running those financial firms.

In his research, Phalippou included rebuttals from private equity firms and a lobbying group that criticized his analysis, noting that investors are "highly satisfied" with private equity performance and disclosures.

Some Ohio teachers disagree. Robin Rayfield, a retired teacher and principal who is executive director of the Ohio Retired Teachers Association, is one.

"The first issue is lack of transparency" in the pension plan's private equity and hedge fund investments, Rayfield said. "We don't know what fee structures and costs are associated with it and how much that investment is worth today. That's not information the public is allowed to have — they say we have confidentiality agreements with the various managers we work with."

'Money for nothing'

The STRS report was conducted by forensic pension investigator Edward Siedle, a former SEC lawyer. It blasts the pension plan's managers for refusing to hand over investment records that beneficiaries need to assess the full costs of the fund's investments and their true performance.

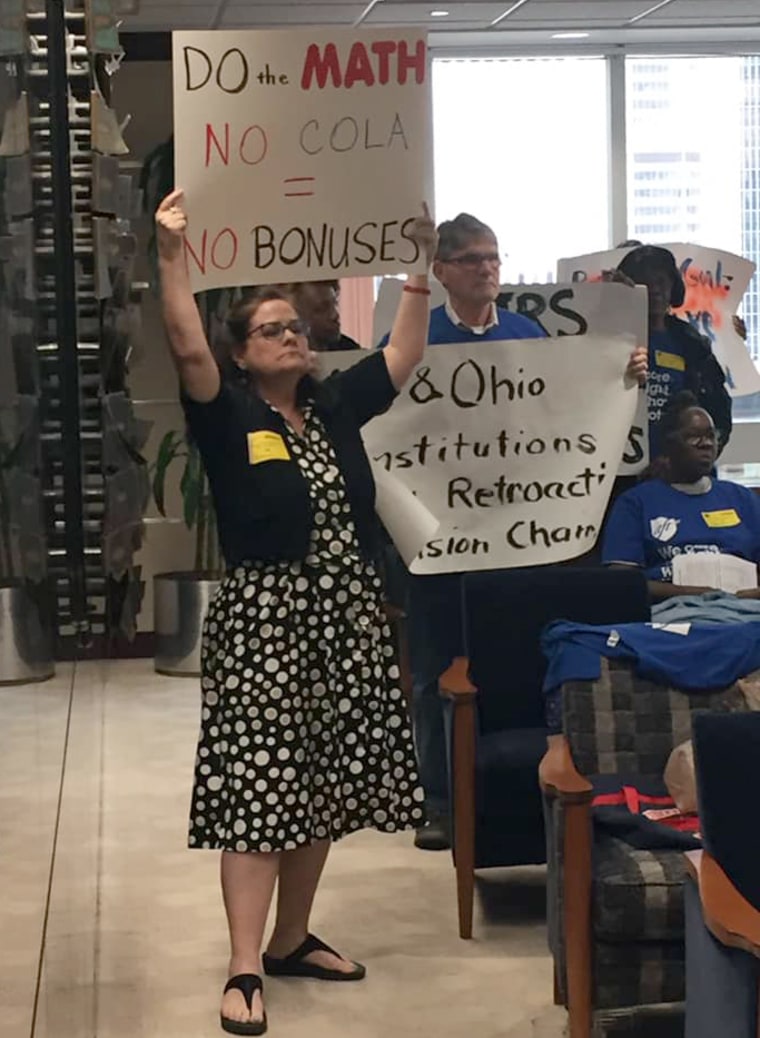

The report raises questions about the pension plan's elimination of the cost-of-living increase, for example. It said the fund might be able to reinstate those payments if it didn't abide by a common practice in the industry — paying private equity managers for money it has committed to invest but hasn't yet deployed. Paying fees on capital committed to a private equity firm but not yet invested is typical among investors in such holdings. The report calls the practice "money for nothing."

If the Ohio fund pays the committed capital fees, it said, halting them could generate $143 million every year, enough to pay the 2 percent cost-of-living increase the pension plan recently eliminated. Because the pension plan hasn't turned over its records, it is impossible to know whether such savings could be generated, the report said.

Every 10 years, Ohio law requires the STRS fund to undergo performance audits conducted by the Ohio Retirement Study Council, a group appointed by leaders of the Ohio House and Senate and the governor. But the last audit was in 2006, 15 years ago, which disturbs many of the fund's beneficiaries.

State Rep. Rick Carfagna, R-Genoa Township, the assistant majority floor leader of the Ohio House, is the new chairman of the Ohio Retirement Study Council. Asked why the audit is five years late, he said in a statement that the delay was due to state pension reform in 2013 and Covid-19. The council put out a request to conduct the audit on May 21, he added, saying, "I'm committed to getting these audits back on schedule and completed in a timely manner."

In the meantime, a problem identified in the pension fund's 2006 performance audit was just remedied this year. The audit found that the fund didn't use a standard measure to assess the performance of its holdings in private equity and hedge funds. Instead, the fund used its own past performance in those areas as its benchmark.

The practice of measuring its performance against its performance is extraordinary, Siedle said. The 2006 audit recommended that the fund apply an external benchmark; starting July 1, it will do so, said Treneff, the STRS spokesman.

"There isn't a perfect benchmark for alternatives," he said. "We thought using the actual performance figure was a neutral position that didn't benefit or harm our performance calculations."

Rudy Fichtenbaum, a retired economics professor at Wright State University in Dayton, just won election to the STRS pension board. His term begins Sept. 1, and he is eager to bring financial expertise to the fund's oversight. He and his wife rely upon their pension income.

Fichtenbaum said that in his own analysis, he found that investing with active managers has cost the Ohio pension plan an average of $380 million a year for a decade. Another concern he has is the risk involved in alternative investments.

"You get taken to the cleaners on your expenses, and you really just have no idea what you're invested in in a lot of cases, he said. "I just don't see how as fiduciaries you can not know where your money is invested."