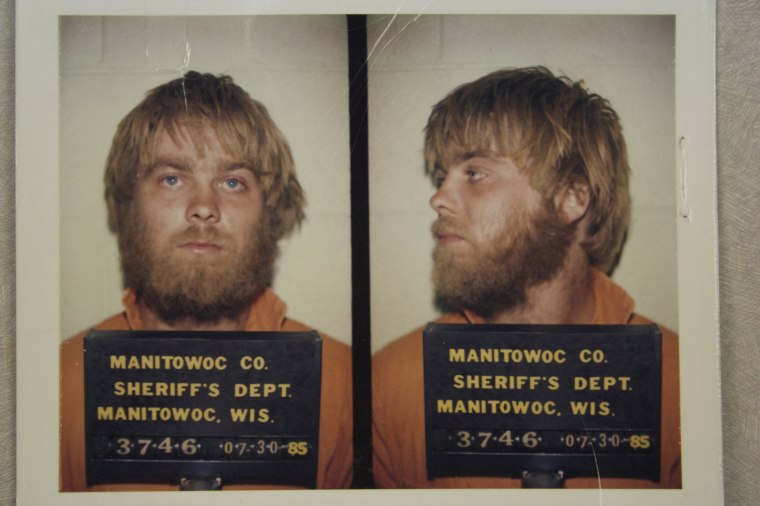

"Making a Murder." "The Jinx." "Disappeared." "The Keepers." "S-town." "Serial." The list of true crime stories is growing, along with the genre’s popularity. The crimes are the type that send shivers down your spine and tend to keep you up at night.

So why do we keep watching?

It’s kind of like our fascination with great white sharks and why we can't turn away from hearing about stories from natural disasters, explains Scott Bonn, PhD, a criminology expert and author of "Why We Love Serial Killers: The Curious Appeal of the World’s Most Savage Murderers."

The shark, the record-breaking earthquake and the serial killer who dismembers his victims and eats them are all very rare, exotic and deadly.

“Serial killers [often the topic of true crime shows] are sort of the worst of the worst,” he says. The shark, the record-breaking earthquake and the serial killer who dismembers his victims and eats them are all very rare, exotic and deadly, Bonn says. “There’s this sort of fascination with things that are larger than life.”

But particularly when it comes to these heinous crimes, Bonn and others have a few theories on why we get so captivated.

There’s the adrenaline factor

Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of why we watch and continue watching true crime is the adrenaline factor. It’s a way to experience the fear and rush that thrill-seekers crave — from the safety and comfort of our couch (where we ourselves aren’t in any real, physical danger).

That’s why the stories tend to be formulaic to a certain extent, Bonn says. “They initially take you into the forest and scare the hell out of you, but then by the end of it they bring you back out of the forest and you’re safe.”

That sense of closure — the mystery getting solved, the killer getting caught — is important, he adds. Bonn compares it to a roller coaster ride. We keep riding because we want that big dip that knocks the wind out of us (the adrenaline release). But we know we’re going to be safe and secure again when the ride ends.

Bonn says he isn’t aware of any specific studies that have measured hormone levels in true crime fans when they watch such shows. But he suspects the adrenaline factor is likely in play based on dozens of interviews he conducted while researching his book with self-defined true crime fans who say the thrill is why they tune in to such programs again and again.

“They absolutely love the thrill of true crime,” he says.

(It’s worth noting that research has neither proven nor disproven adrenaline rushes are addictive, but some evidence does suggest that when thrill seekers’ brains are stimulated like they might be during a “rush,” parts of the brain known to be linked to the addiction cycle are in fact more active compared to people who were not thrill seekers, according to MRI scans.)

We want to make sense of the senseless

There’s also the need to understand the perpetrator, and make sense of what might make someone do the horrendous things that serial kills do.

We all go about our days under the pretext that we and the people around us will follow certain rules. We don’t hurt each other. We don’t enter people’s homes without their permission. When people break those rules, we want an explanation. What warped that individual’s perception of right and wrong? And could something come along that might similarly warp our perception of right and wrong?

“To simply reduce it and say, ‘Oh they’re just pure evil misses so much of it,’” Bonn explains. These individuals are human beings and there’s always a why behind their motivations, needs, and desires, he says.

It begs the question: What might I be capable of under such circumstances?

This understanding of criminal behavior is rooted in the functionalism theory in sociology that everyone in society — even the worst among us — have a purpose, Bonn says. Deviants and criminals set the outer boundaries of what is acceptable and what is not.

“We’re fascinated by testing and exploring these boundaries of human nature,” Bonn says. And in part because doing so forces us to look at ourselves, too.

“It begs the question: What might I be capable of under such circumstances?” Bonn says.

It may feed an evolutionary survival instinct

Another theory is that true crime stories give us information we (potentially subconsciously) register as something that may at some point help us survive (on the off-chance a serial murderer shows up at our front door).

A 2010 study published in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science investigated our motivations for seeking out “true crime” stories (and is one of the few peer-reviewed studies to have done so).

The data showed that women were more likely to be drawn to true crime stories than men (when given the choice between different genres). And another set of experiments suggested that women were more likely to choose a true crime story than men when they expected to learn something that might help protect them if they found themselves in a perilous situation, when they expected to learn something about why the killer committed the crime, and when the victim of the crime was female.

Together the research suggest women are choosing these stories if and when they might learn something that would help them survive if they were ever in a similar situation, explains study co-author Amanda Vicary, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at Illinois Wesleyan University.

“If someone knows what drives someone to kill and knows how to escape if kidnapped, obviously their chances of avoiding or surviving a crime are much higher,” she says. (Interestingly, research shows that men are actually more likely to be victims of a crime than women, but that women do tend to have more fear that they will be a victim of a crime than men do.)

These motivations are likely subconscious ones, Vicary adds. “If you asked most women why they like true crime, they probably wouldn’t list these reasons,” she says. “But their innate fear and desire for survival may be driving their interest in crime.”

Watching true crime stories can be cathartic

Another theory of his (based on the sociological research he’s done interviewing true crime fans) is that the genre provides an emotional catharsis for fans.

We get to experience fear without ever really being in danger. Wrongs are righted. “It’s a morality play,” Bonn says. “We can’t have that in real life. Real life is more complex and uncertain.”

MORE FROM BETTER

- Your brain on a diet

- Smiling can trick your brain into happiness (and boost your health)

- Your brain on prayer and meditation

- The science behind being 'hangry'

Want more tips like these? NBC News BETTER is obsessed with finding easier, healthier and smarter ways to live. Sign up for our newsletter.