Donald Trump may be the most entertainment-driven president in American history. But he has a celebrity problem: his own.

In many ways, Trump is not unlike previous presidents who used the power of entertainment to win the White House. Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan all connected directly with voters by using new media technology to bypass the press and their party’s establishment. During the 2016 election, Trump combined reality-TV style with social media flair. His impulsiveness, outspokenness and arrogance made for great television and, surprisingly to seasoned politicos, translated into votes.

For these past presidents, however, publicity was a tool — not the end goal. They used entertainment strategies on the campaign trail to sell themselves. But once elected, they applied these tactics to sell a legislative agenda to the public, not a persona.

In the Oval Office, however, Trump is still preoccupied with himself. He talks often about his ratings, his brand and his crowd size. Unlike his media-savvy predecessors, Trump has yet to translate his persuasive showbiz campaign style into an effective leadership strategy.

Over the 20th century, the evolving advertising, public relations, and entertainment industries have given American presidents more ways to connect directly to voters. Presidents often worked with controversial figures and deployed risky strategies. But their goals in doing so from the Oval Office were largely policy driven.

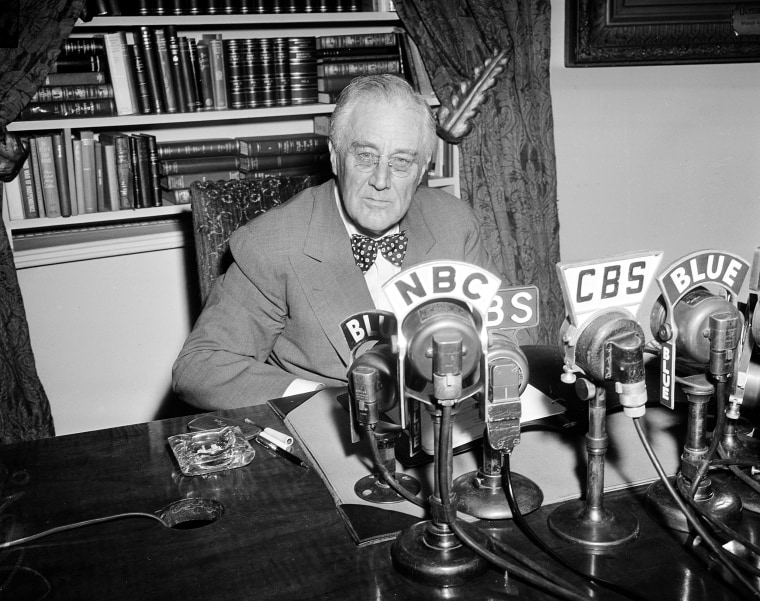

Consider Franklin D. Roosevelt. Though his “Fireside Chats” have become legendary, Roosevelt’s collaboration with the motion picture industry was particularly innovative. His work with Hollywood was so effective, in fact, that critics feared it was dangerously close to the “dark magic” of Nazi Germany’s propaganda machine.

FDR’s Republican predecessors, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, had both experimented with advertising agencies and radio shows to get elected. But Roosevelt went one step further and turned to a controversial new entertainment medium — Hollywood — to bypass his critics in journalism and speak directly to the American people about his New Deal programs.

These ties were clear on the campaign trail. For example, Roosevelt’s friend and supporter, movie mogul Jack Warner welcomed the Democratic presidential nominee to Los Angeles with a huge parade spectacle in September of 1932. And the alliance continued after FDR won the White House. Warner rallied other studio chiefs to make short promotional films for New Deal legislation to be shown in movie theaters across the country.

This was risky for Roosevelt. At a time when anti-Semitism was a deeply ingrained aspect of much of American society, the movie industry was largely run by Jewish immigrants. In addition, powerful Christian groups organized boycotts of films they saw as corrupting America’s youth. Roosevelt, however, remained close to an industry viewed by many elites as “seedy,” because he recognized that movie audiences were the very people he needed to reach: ethnic immigrant workers.

To help sell the New Deal’s alphabet programs Roosevelt also brought in political outsiders who were media experts. Reporter Stephen Early became the White House press secretary and negotiated the administration’s relationships with the press. Robert Sherwood, a celebrated playwright, signed on as presidential speechwriter. Former journalist Lowell Mellett ran the National Emergency Council during the Great Depression, then worked his way up the New Deal ladder to head the Bureau of Motion Pictures during World War II. These media pros helped make Roosevelt and his New Deal famous around the globe.

As television sparked political imaginations, it seemed clear that image control was a political and ideological weapon.

In the postwar era, both Republicans and Democrats tried to emulate Roosevelt’s strategies. As television sparked political imaginations in America and the Cold War intensified abroad, it seemed clear that image control was a political and ideological weapon. It could win elections at home and fight off communism abroad.

As a result, efforts to harness a professional celebrity production team became a part of political campaigns and the presidency itself. Yes, President Dwight D. Eisenhower was the general who led U.S. troops to victory in World War II. But his image as a trusted political leader was carefully managed by a team of advertisers and entertainers. Eisenhower drafted movie star Robert Montgomery to formally control presidential image-making, and built a production studio in the White House itself.

Kennedy shifted this into high gear. His innovative 1960 campaign made the Hollywood “Dream Machine” essential to winning the presidency. Kennedy’s political team brought in filmmaker Jack Denove to capture the charismatic candidate’s interactions with voters, and wrangled Frank Sinatra to croon the campaign soundtrack.

This was expensive. It aroused suspicions from elders within the Democratic Party, like Eleanor Roosevelt. But it was also effective. And it didn’t stop in November. Kennedy used the platform of the presidency — and his glamorous friends — to sell ideas that resonated with the public and eventually shaped policy. (Though it was the legislative-savvy Lyndon B. Johnson who ultimately enacted much of it.)

Following Kennedy’s success, the political arena opened to new faces who were political amateurs in the traditional sense — but skilled showmen. Cue Ronald Reagan.

The California governor was no political fraud. In studying his political ascendency during the 1960s, one publication noted that Reagan’s success was rooted in a “political style that is well suited to the age of mass media.” Reagan articulated a message people wanted to hear. How? He used images and rhetoric the public had been watching for years — in movie theaters and on television.

Yes, Reagan could memorize lines and deliver impassioned speeches. But, as he made his way from Hollywood actor to General Electric TV spokesman to GOP rising star, he honed a message that resonated with fans — who were also voters. His stories of stoic heroes conquering all odds to secure happiness and freedom followed the optimistic storyline that Hollywood studios had long churned out.

One astute — and envious — rival, Richard M. Nixon tried to analyze what made the California governor so effective. He “reaches the heart,” Nixon observed as he was gearing up for his 1968 presidential run. “We reach the mind … Do we not miss an opportunity in failing to reach the hearts and not just the heads?”

This is one reason entertainment has proved so effective in American politics. It is not just about delivering the right market-tested lines during a campaign. Successful presidents must also connect emotionally through shared stories to sell a legislative agenda.

In the Oval Office, Reagan continued using the silver screen to communicate with the American people. He explained key policies by talking about “Rambo,” “Star Wars” and battles between good and evil. He employed a full-time media team to control, monitor and protect his public image, frequently staging the news to benefit his governing priorities.

For Trump the question remains: What now?

Can Trump transform his fascination with his own celebrity into a policy that will resonate with voters? He won the presidency with his reality-TV appeal, but his pre-occupation with personal ratings and self-promotion have infringed on his ability to govern with coherence, rather than enhanced it. Controversial actions like pardoning former Sherriff Joe Arpaio, and his social media campaign to build up suspense around it, reveal Trump’s desire to promote himself — not policy initiatives.

A successful campaign can hinge on personality, but a successful presidency requires substance and legislation. If Trump continues to focus on simply remaining the world’s top celebrity, with the highest TV ratings, he will likely join officials like James Buchannan and Andrew Johnson — at the bottom of the presidential ranking list.

Kathryn Cramer Brownell is assistant professor of history at Purdue University and the author of "Showbiz Politics: Hollywood in American Political Life."