In 2010, communications scholar Safiya U. Noble was looking for websites to share with her stepdaughter and nieces. She searched "black girls" on Google, expecting to be directed to educational sites, historical information, or pop culture sites for young people.

Instead, the first hit was the site HotBlackPussy.com. The first page was filled with similar results. According to Google in 2010, "black girls" were defined not by history, interests, or aspirations. They were defined as porn.

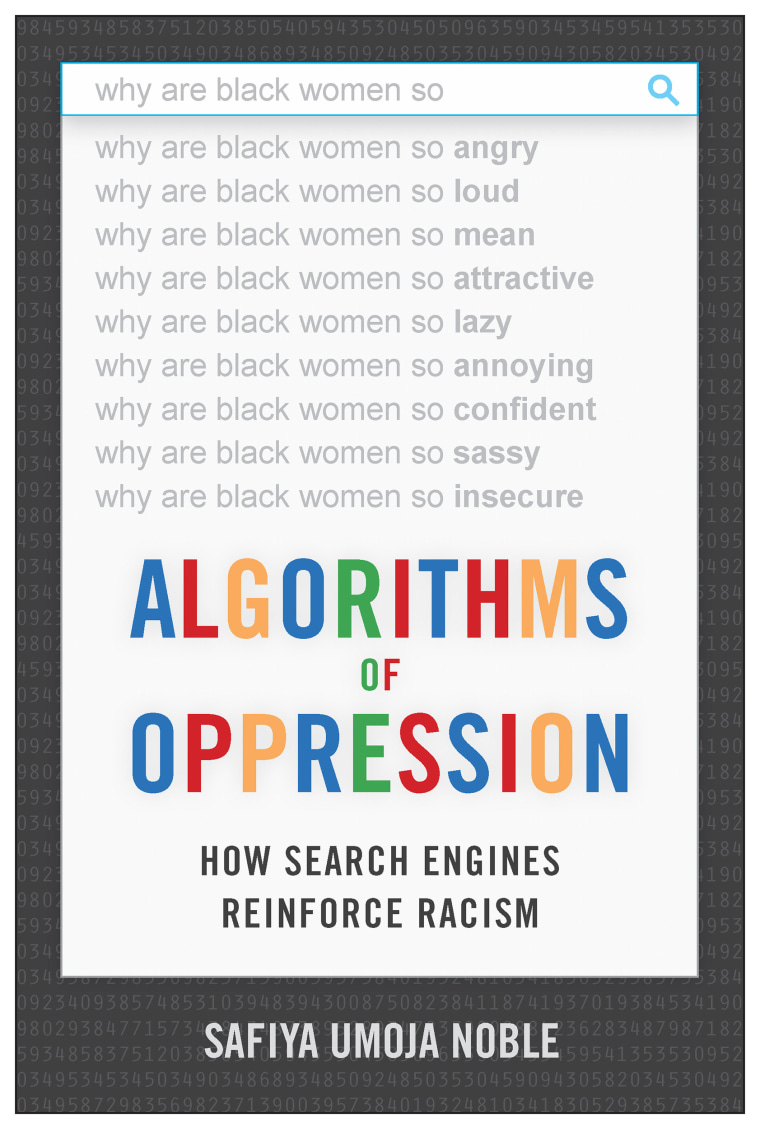

What accounts for such racist, sexist search results? Most people tend to attribute Google failures or glitches like this to public search patterns; search engines return porn for "black girls" because those are the sites that people click on most. But based on her own experiments with Google search and on the scholarly literature related to search engines, Noble thinks this rationale is too simplistic. In her new book, "Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism," Noble points out that search engines are not magically impartial arbiters. Search algorithms are created by people and reflect, not just the racist and sexist biases of users, but the racist and sexist biases of their designers.

"It’s insufficient to declare search results to be simply a matter of what users do online," Noble told me by email. "Certainly that is part of it, but more importantly, Google is an advertising platform and its customers or advertisers are looking to optimize their content, products, and services. This means that certain words, including various identities and communities, can be optimized to link to all kinds of nefarious content."

Google isn't necessarily focused on giving users the most trustworthy or balanced information, Noble argues. She points out that Google makes the vast majority of its income from ads — more than 85% of its income in fact. "What shows up on the first page of search is typically highly optimized advertising-related content," Noble explains in her book, "because its clients are paying Google for placement on the first page either through direct engagement with Google's AdWords program or through a gray market of search engine optimization products."

"Algorithms of Oppression" discusses a number of other disturbing examples where search results seem optimized to spread prejudice rather than accurate information. For example, searching for information about Jewish people or history often leads to anti-Semitic websites. In late 2016, the Guardian's Carole Cadwalladr tried to search for information about the Holocaust. The top result for the question "Did the Holocaust happen?" was the Nazi site Stormfront. Cadwalladr concluded that Google was prioritizing popular results rather than more reliable ones such as Wikipedia, because organizing searches by popularity is appealing to Google's advertisers.

Google's stranglehold on information, and the public's assumption that Google information is reliable and neutral, can cause concrete harm. There is evidence that accounts connected to the Russian government bought ads on Google related to the 2016 election, for example. The goal of these ads was uncertain, but it points to the possibility that foreign powers or interested parties could actively try to influence Google results to affect election in the same way they attempted to spread disinformation through Facebook and Twitter.

Search algorithms are created by people and reflect, not just the racist and sexist biases of users, but the racist and sexist biases of their designers.

In her book, Noble also points out that reports on Dylann Roof's manifesto reported that he was radicalized by a Google search. Roof, a white supremacist who murdered nine black people in a Charleston church, wrote in 2012 that he "typed the words 'black on White crime' into Google, and I have never been the same since."

The first result Roof got was for the website of the Council of Conservative Citizens, identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a white supremacist organization. This site falsely presented black people as engaged in frequent violent assaults on white people. Roof noted that his Google search discovery led him to be "racially aware," and fueled his hatred of black people.

When Noble reproduced Roof's search in 2015, she discovered that searching for "black on white crimes" still led to racist hate sites. Noble points out that neither her search nor Roof's included links to FBI statistics showing that the overwhelming majority of crime against white people is committed by white people. We need our search engines to help challenge the assumptions of people like Roof with facts, not feed their hate.

So how can we get better, less racist search results? Google is somewhat susceptible to public pressure. After Noble wrote an article discussing the results for "black girls" in 2012, the search engine quietly tweaked its algorithm to move porn results off the first page for the search. But Noble argues that hoping for voluntarily change isn't sufficient.

"I think we should be thinking about corollary public information portals that are curated by librarians, teachers, professors, and information professionals who are better trained to think about the harm caused to the public—particularly to vulnerable populations, when misinformation flourishes," Noble says.

The government invests in public radio and public television in part to make sure that pubic airwaves are used in part for the public good. The Federal Communications Commission regulates television and radio for the same reason. Google, with its virtual monopoly on web search, arguably has more power over knowledge and information than television or radio in the modern era. Noble, and others, a strong case for public competition, and for greater public oversight.

In the meantime, Noble's book may at least raise public awareness. Google search results are not objective truths, and those who use the service should be aware of its biases.

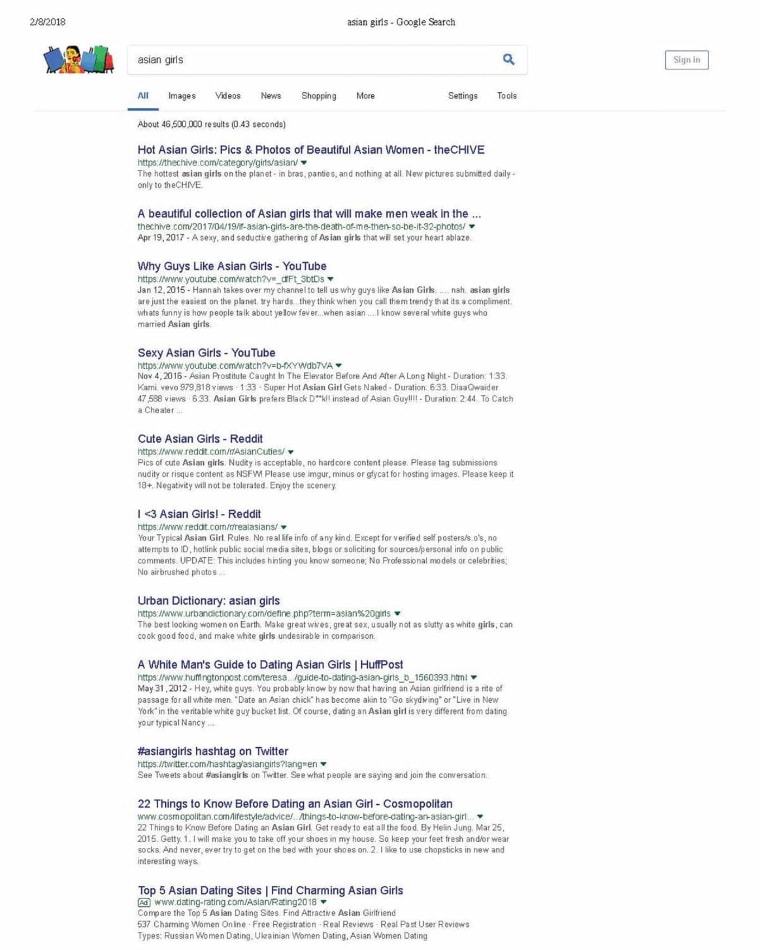

The first result for "black girls" now is the site Black Girls Code, which encourages black girls to enter computer science. If you type "Asian girls" into Google though, the search engine’s top results are almost all related to fetishizing and sexualizing Asian women. "Google search is excellent for certain kinds of information — like where the closest coffee shop might be, or for other kinds of banal information," Noble says. But for information about marginalized people, "there is a lot of work still to do."

Noah Berlatsky is a freelance writer. He edits the online comics-and-culture website The Hooded Utilitarian and is the author of the book "Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948."