WASHINGTON — The Trump administration has stopped an Obama-era rule requiring large companies to report how much they pay workers by race and gender.

The rule was intended to help close the persistent wage gap between men and women, as well as between racial groups, through greater pay transparency.

In halting the rule, which was supposed to take effect in March, the Trump administration said it simply wouldn’t have worked.

"While I believe the intention was good and agree that pay transparency is important, the proposed policy would not yield the intended results," said Ivanka Trump, the president's daughter and adviser, who came to Washington promising to fight for working women.

Neomi Rao, head of the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, explained the decision in a memo, saying the requirements "lack practical utility, are unnecessarily burdensome, and do not adequately address privacy and confidentiality issues."

Trump and Rao both echo the criticisms of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Retail Federation, and other major business associations that have lobbied against the rule since its inception. In a March letter to Mick Mulvaney, the White House budget director, a coalition of business groups argued the new reporting requirements would be overly burdensome and would not yield useful information. "This data will be of no utility," the coalition concluded.

But supporters of the rule said the very act of reporting this information would have forced companies to be more conscious of pay disparities and encouraged them to take voluntary corrective measures.

"If you look at companies that already have to monitor themselves or monitor themselves voluntarily, they typically do find issues that need fixing," said Ariane Hegewisch, program director at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a Washington-based think tank.

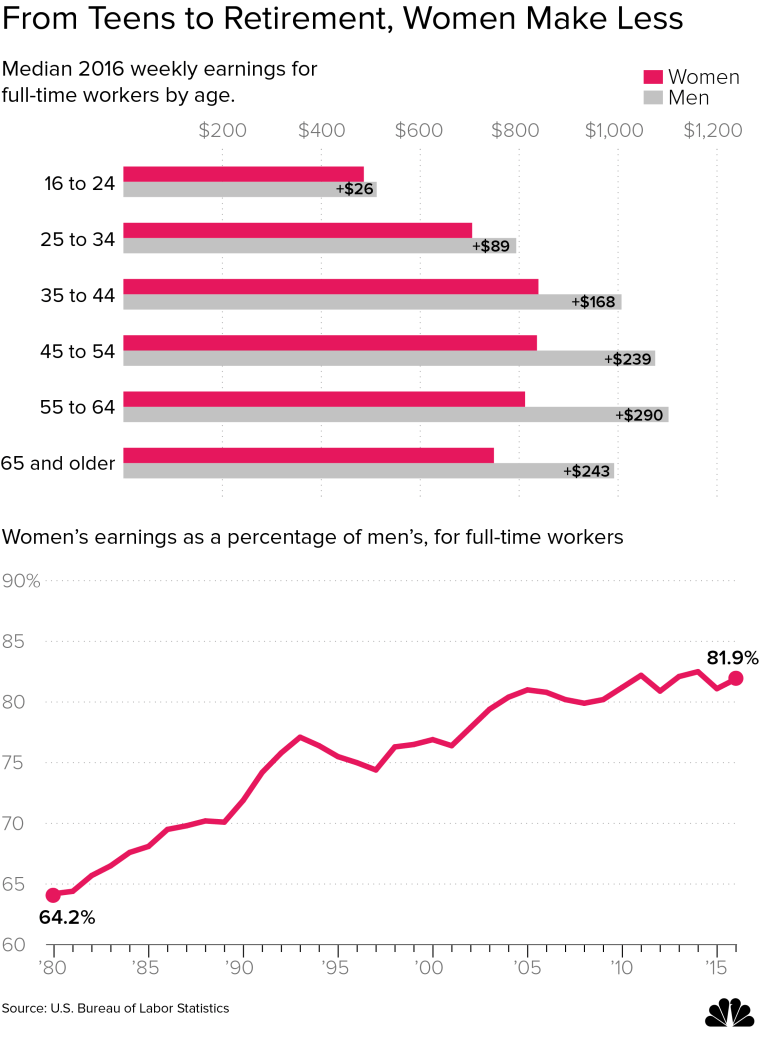

The gender pay gap has been closing over time, but it remains significant. Among full-time workers in 2015, women’s earnings were 81 percent of men’s, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In a recent study, Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn found that 38 percent of the wage gap may be due to discrimination, rather than differences in occupation, work experience, education and other individual choices.

Pamela Coukos, a former Department of Labor official who helped develop the Obama-era rule, argued that employers who are required to be more transparent tend to have smaller pay gaps, pointing to unionized workforces and public-sector employees.

In the federal government, where salary information is public and pay scales are highly structured, the gender pay gap for white-collar workers shrunk from 30 percent in 1992 to 13 percent in 2012, according to a 2014 report.

"What gets measured gets done," Coukos said. "Not having data is a big limitation."

What Obama's Plan Would Have Done

Under the Obama-era rule, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission would have used the data to help investigate complaints and flag pay disparities for further inquiry. To protect privacy, data about individual firms or employees wouldn’t have been made public, but the agency would have released aggregate data about pay in different industries, broken down by race and gender.

Critics of the rule say the data itself is the problem, arguing it wouldn’t be precise enough to be useful. In an effort to reduce the burden on employers, the rule would have classified employees according to 10 broad categories.

A hospital, for example, would have to group together nurses, lawyers and doctors under the single category of "professionals," the Chamber of Commerce commented last year.

"It would have provided what could possibly be misleading information," said Paul White, a labor economist for consulting firm Resolution Economics. "The ultimate goal is to compare employees that are similarly situated."

Coukos counters that the rule was never intended to provide conclusive evidence of pay discrimination; it was simply meant to be a starting point for further investigation. Even extremely broad data sets could help reveal "how folks are doing when measured against their peers," she adds.

Despite the White House’s inaction, a growing number of states and municipalities are passing new laws requiring pay transparency for government contractors, and employees themselves are pushing for greater salary disclosure.

"It’s not going away — the culture around keeping that secret is breaking down rapidly," says Coukos.