PHILADELPHIA — "You're great!" That's what every student hears from teacher Herman Douglas when they enter his seventh-grade class at Mary McLeod Bethune Elementary School in a neighborhood of North Philadelphia plagued with crime, violence and poverty.

"I'm great," each student responds.

Douglas’ strong positive message is meant to counter the negativity so many students pass by in the streets on their way to school. He also bestows titles on his students, referring them as “king” and “queen" as reminders that they're descendants of African royalty.

In addition to Douglas, 12 other African-American male educators work at this school — that's nearly 30 percent of the staff at a school where the students are primarily black and Hispanic. That number stands in contrast to the rest of the nation, where only 2 percent of teachers are African-American men.

For the past few years, this school has been trying to change the face of teaching to address what’s seen as a fundamental problem facing students in this part of Philadelphia.

"We have a lot of children where they have mom at home, they have grandma, but they don’t have dad, uncle’s not around," said principal Jamina Clay-Dingle, who has made it a point to recruit black men to her classrooms. "It was a deliberate decision that we wanted to put representation in front of our students who looked like them."

Studies show that minority children perform better in school when their teachers are diverse. If a black boy has even just one black teacher in grade school, recent research predicts he has a significantly improved chance to graduate high school and consider college. Many minority educators also believe teaching students of various ethnic backgrounds breaks down stereotypes and generates tolerance.

As the school year winds down at Bethune, educators say students face higher expectations, attendance is up, and they expect test scores and graduate rates to soon follow.

Douglas, who’s been teaching here for nine years, called his job "a mission to save as many students as possible."

"I've been that child under the desk crying because my father wasn’t around," he said. "I know what it’s like when you want nice sneakers, a nice car ... and you don’t have any of those things and you have to think about stealing it."

Douglas grew up not far from Bethune, in a community where crack cocaine and temptation were everywhere. In school, he admits to being a "problematic student" who, by eighth grade, was cutting classes, talking back to teachers, and getting suspended all the time. But he turned his life around, finished school, graduated from college, and became a teacher.

His presence, like that of his black male colleagues, Douglas believes, speaks volumes to his students.

"We need us in these buildings to show our students how to be a man or to show the young ladies how a man acts toward them in an appropriate manner," he said.

His students seem to be learning those lessons.

"He can relate better because we’re going through things he already went through,” said Genav Sosa, a student in Douglas' seventh-grade class. “He also makes it well known that life isn’t fair so you gotta work hard."

Pharad Gardner, a classmate, agreed. "He doesn’t try to sugar coat anything. He’ll tell us the truth," he said.

Dr. William Hite, Philadelphia's superintendent of schools, said that 400 of the city's 10,000 teachers are African-American men. That's 4 percent, or double the national average, but it's just a start, added Hite, who is African-American.

"Children feel like they not only have mentors and role models but they have advocates," he said. "We can do a much better job of making sure our educational workforce is a closer representation to the population we serve."

The superintendent also belongs to an organization called the Fellowship, a professional networking group of more than 600 African-American male educators mostly in Philadelphia. Along with various recruitment events, each Fellowship member is personally mentoring a student in high school or college and leading them down the path toward teaching.

The group's goal is to more than double the number of black male teachers in the city to 1,000 by 2020.

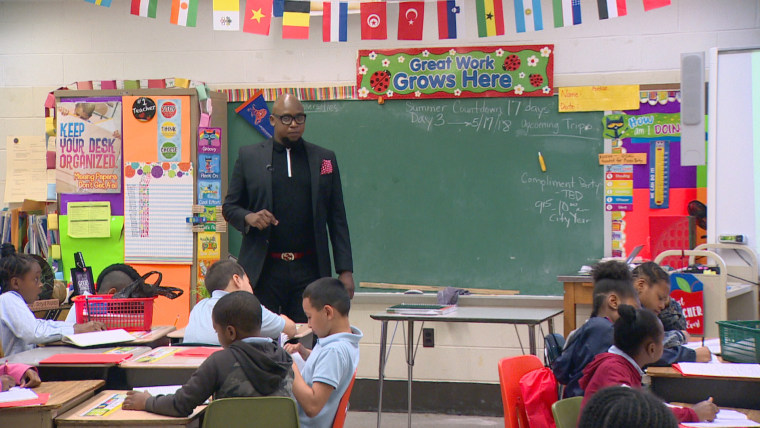

Deighton Boyd is among the African-American teachers at Bethune trying to reinforce a culture of success and achievement.

His fourth-grade class starts each morning by reciting well-known lines of affirmation by the African-American poet Useni Eugene Perkins: “Hey Black Child/ Do you know who you are/ Who you really are/ Do you know you can be/ What you want to be/ If you try to be/ What you can be?”

"I’ve made it very clear to my students that, when I was growing up, I didn’t have a lot of material things. I grew up in a struggle," Boyd said.

He said that some of his students call him "dad."

“It inspires me to come to school every day," Boyd explained. "A lot of our students deal with traumatic experiences ... you got to know how to respond to that type of situation."

CORRECTION (June 16, 2018, 7:40 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misidentified a teacher in a photo caption. He is Deighton Boyd, not Herman Douglas.