Doctors in the U.S. should be on the lookout for cases of Marburg virus, a rare but deadly infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in an alert on Thursday.

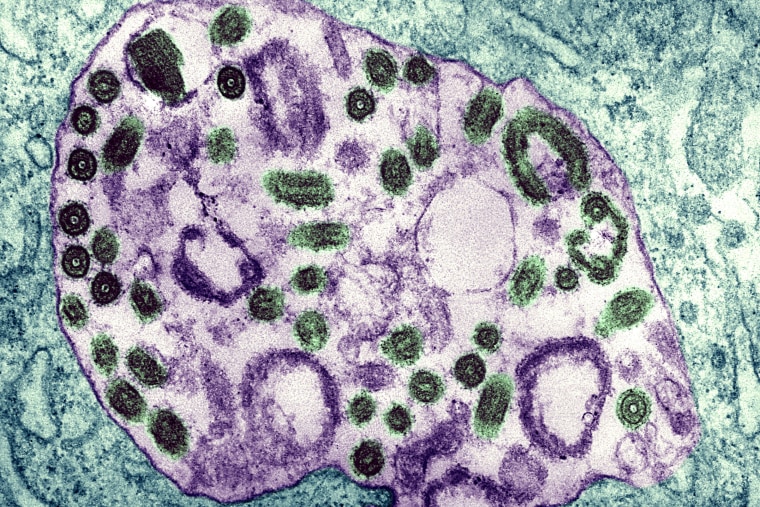

Marburg belongs to the same family as Ebola; both diseases are viral hemorrhagic fevers — conditions that can cause internal bleeding and damage multiple organ systems.

The CDC's new health advisory, sent to clinicians and public health departments, came in response to recent Marburg outbreaks in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania. Neither country had reported cases prior to this year.

Tanzania’s health ministry announced on March 21 that a cluster of Marburg cases was confirmed in the northwest Kagera region. As of Wednesday, the country had identified eight cases in connection to that outbreak, five of which were fatal. All the cases appear to be linked.

Equatorial Guinea, meanwhile, confirmed 14 Marburg cases between Feb. 7 and April 5, according to the CDC. Ten of those were fatal.

Past outbreaks of Marburg and Ebola have had death rates ranging from 25% to 90%, depending on the virus strain and the strength of efforts to control transmission. The diseases’ average death rate is around 50%, according to the World Health Organization.

Although the risk of Marburg virus disease in the U.S. is low, the CDC is asking doctors to “be aware of the potential for imported cases.”

Evaluating Marburg’s public health threat

George Ameh, the WHO’s representative in Equatorial Guinea, said in February that the country’s first case most likely dated back to Jan. 7, and that the deaths were among close family members and people who attended their burials.

But the CDC said Thursday that cases in one particular province of Equatorial Guinea do not seem to be linked to one another. In total, four provinces have detected cases thus far. For those reasons, the CDC said, “there may be undetected community spread of the virus in the country.”

Amira Roess, a global health and epidemiology professor at George Mason University, said Marburg cases appear to be more prevalent and widespread in the current outbreak compared to past ones.

“We’re definitely seeing an increase in those more severe cases and we’re also seeing just more transmission in the areas where we haven’t seen these viruses before,” Roess said, referring to both Marburg and Ebola. “It is concerning.”

Migration patterns that have increased movement from rural to urban areas, as well as within and between African countries, could play a role in the trend, she said. Roess added that humans are also encroaching on areas that were previously only inhabited by wildlife.

Marburg cases can look similar to Ebola. Symptoms usually start with a fever, chills, headache or muscle aches, followed by a rash along with nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Some patients may also get a sore throat or chest or stomach pain.

Ebola symptoms follow a similar progression from “dry” to “wet." Symptoms of either disease can develop anywhere from two to 21 days after a person is infected.

People can spread Marburg virus through bodily fluids, blood and contaminated objects or surfaces. The virus does not spread via airborne transmission.

No vaccine or antiviral treatment is approved to treat Marburg, but the CDC said that 32 laboratories and eight regional treatment centers in the U.S. can test for the disease.

Fruit bats are Marburg's original hosts, and the first human case was detected in 1967. Prior to this year's outbreaks, the most recent cases were in Ghana, where two deaths and one additional infection were reported last year. Before that, Guinea reported one death in 2021.

The U.S. reported one case in 2009 in a traveler who'd returned from Uganda the year before and was diagnosed post-recovery.

Roess said increased testing capacity in Africa has likely helped health officials detect more cases in the current outbreaks. But she added that there may still be issues with underreporting.

When health officials see a province like the one in Equatorial Guinea with cases that aren’t epidemiologically linked to others, she said, “what it tells me is that we are not able to collect good information or data, even though we have the technology to do that.”

The CDC has issued a level 2 travel alert for Equatorial Guinea, meaning visitors should avoid nonessential travel to provinces that have reported cases. Travelers to Tanzania should exercise standard precautions like steering clear of sick people and monitoring for symptoms, according to the CDC.

The WHO said in February that it hopes to test an experimental Marburg vaccine in Equatorial Guinea. Three vaccine developers have said they could probably make doses of their candidates available to test in the current outbreak. Two of those experimental vaccines have already gone through phase 1 clinical trials.