Bulldozed and bisected:

Highway construction built a legacy of inequality

Will their removal heal historic wounds?

This audio interactive is best experienced with headphones

By Suzanne Gamboa, Phil McCausland, Josh Lederman and Ben Popken

June 18, 2021

During the largest public works program ever attempted in the United States, Black and Latino communities in cities across the country met the blade of the bulldozer and the crush of the wrecking ball, making room for ribbons of new highway. Whether through blindness or design, the mid-century American interstate highway program demolished homes and bisected communities, driven by the promise of prosperity, faster commutes and jobs.

“Everything we needed was in our neighborhood,” said Barbara Lacen-Keller, 75, a lifelong resident of Tremé, a once bustling New Orleans community that Interstate 10 cut through in the 1960s. “The highway really destroyed that.”

What has changed decades after the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 brought 41,000 miles of interstates to the country is the recognition of the harm that was done to communities left in the shade of these now-aging roadways. From 1957 to 1977, the program displaced over 475,000 households and 1 million people, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Now, as many of these hulking structures reach obsolescence, the federal government and many states and cities are belatedly recognizing the harm they caused, and are working with communities to design alternatives that repair the damage. But in many cases, those plans are reopening old wounds and leading to protracted debates that politicians and engineers are struggling to solve.

Of more than 50 interstate highways across the country nearing the end of their life span, NBC News examined three urban neighborhoods that show the range of proposals underway to redress the harms caused by the construction of interstates.

- In Syracuse, New York, the 15th Ward, home to many Black residents, disappeared under the shadows and smog of Interstate 81. New York state has committed $800 million to the first phase of the highway’s removal beginning next year, to be replaced by a walkable and bikeable “community grid.” But residents are deeply concerned about displacement, gentrification, and the negative impact on other areas.

- In New Orleans, bustling Black-owned businesses in the Tremé section closed one by one as the Claiborne Expressway’s gray cement pillars replaced stately white oaks that had lined the avenue. President Joe Biden cited the removal of the expressway as part of his goal of addressing “historic inequities” within infrastructure. But many longtime residents are so concerned that the removal will lead to gentrification that they don’t want it torn down.

- In Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights neighborhood, a vast maze of highways took the place of beloved family homes and cut many Latino residents off from their schools, churches and one another. The pollution from the multiple highway interchanges has severely damaged the air quality in the neighborhood, and residents want sound-blocking walls, and better air filtration in schools and buildings.

In an April interview with The Grio, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said the highway system was built in ways that embedded racist principles, and the $20 billion in Biden’s budget proposal contains funding to stitch some of these neighborhoods back together.

But the practical implication of that remains unclear.

“We can’t be guilty a third time of displacing people,” said Khalid Bey, who is running for mayor in Syracuse, referring to past urban renewal projects. “Our city has done that twice already. And the highway, tearing it down, can’t become an excuse for doing it either.”

The future of what lies ahead in each community — whether it’s highway removal or neighborhood revitalization — varies and, for many, remains uncertain. But what’s clear is that many residents in each of these neighborhoods are working to ensure the same harm doesn't come to their communities.

15th Ward

Syracuse, N.Y.

Interstate-81, Interstate-690

Bey knows that history has a way of repeating itself. This time, he hopes it won’t.

First it was the mass relocation of Black residents from Syracuse’s bustling 15th Ward in the middle of the last century in the name of “urban renewal” of the city’s “slums.” Then in the 1960s came Interstate 81, and a 1.4-mile stretch of raised highway that plowed through the community, delivering a fatal blow to the neighborhood and wiping the 15th Ward off the city’s maps.

A woman walks past Schor’s Meats at 604 Harrison Street in 1963. (Onondaga Historical Association)

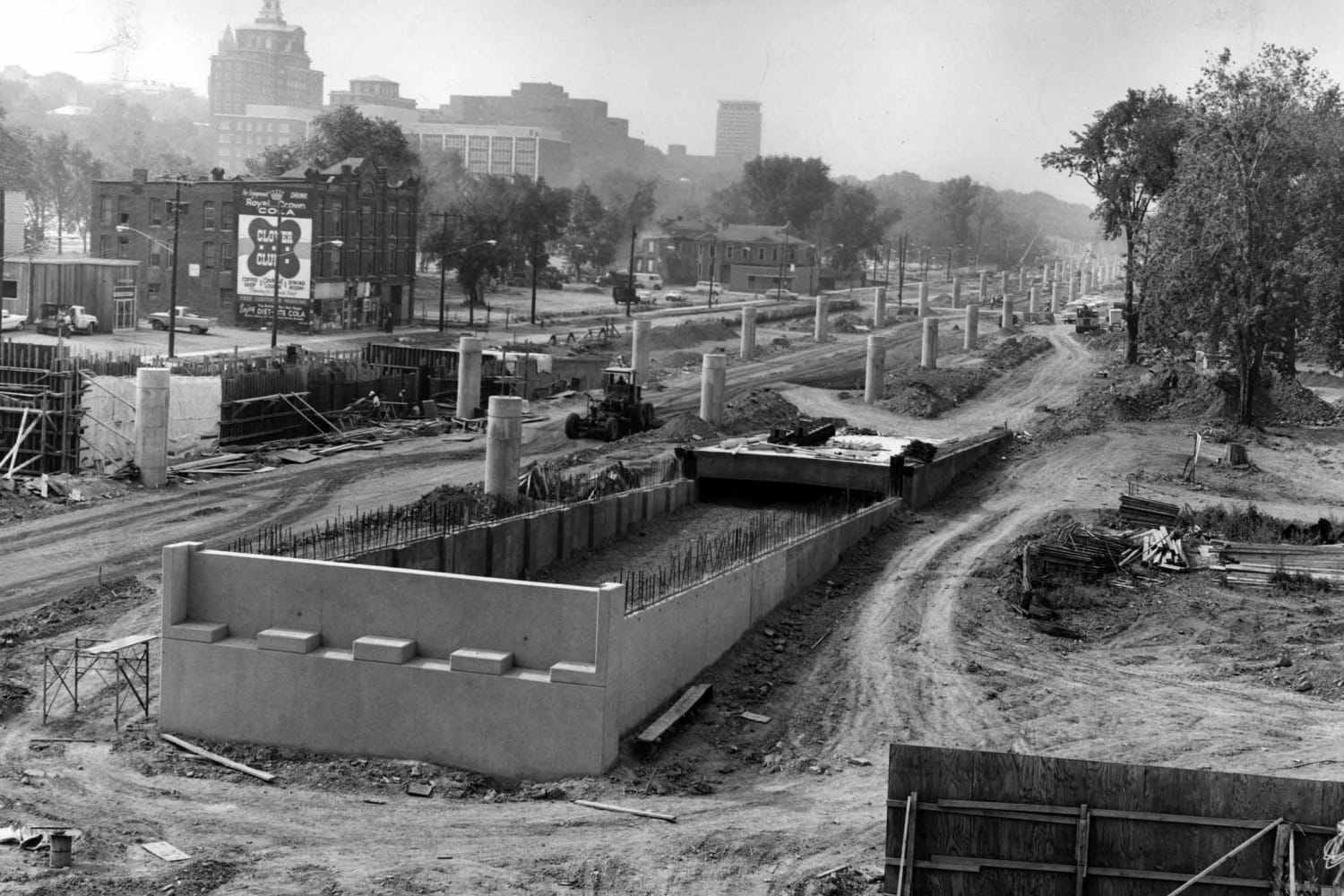

Highway construction through the 15th Ward in 1965. (Onondaga Historical Association)

Highway construction in 1966. (Onondaga Historical Association)

Along the way, Bey’s grandfather lost his convenience store as local owners were forced to sell, many through eminent domain when the state seized their property. The land where his mother’s childhood home once sat, Bey said, is now a state psychiatric hospital.

Now as the state and federal government prepare to tear down the decaying viaduct — deemed “obsolete” — starting next year, Bey fears it could all happen again.

“Everything over there was torn down – everything,” Bey, 40, said.

Khalid Bey at Central Village in Syracuse, N.Y. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

Khalid Bey at Central Village in Syracuse, N.Y. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

He interrupts himself with bellowing coughs, and apologizes, wondering aloud whether his respiratory issues might have something to do with a childhood spent breathing in interstate fumes.

The numbers tell a harrowing story. State health data shows that asthma-related hospitalizations are twice as high in Syracuse as the county as a whole. A 2015 study using U.S. Census data found that among America’s 100 largest cities, Syracuse had the highest concentration of poverty among Blacks and Hispanics, with poverty rates well upward of 50 percent in the tracts surrounding the viaduct.

Once a haven for Blacks lured from the South in the 1900s by Syracuse’s manufacturing boom, the swath of deserted roads, housing projects and hospital parking lots now seems as weathered as the highway that looms above it, ferrying some 100,000 vehicles per day, state transportation department statistics show.

Now several years past its functional expiration date, the interstate has become a physical border dividing the community along all-too-familiar lines: Mostly Black and poor to the south and west; wealthier and mostly white to the east, where the private Syracuse University sits.

As New York state plans to rip the viaduct down and the Biden administration pledges that part of its proposed $20 billion infrastructure plan will go to reconnecting the community, a fierce debate has broken out over unintended consequences, and whether a story of “urban renewal” gone awry is about to be repeated.

View from under the viaduct of the Pioneer Homes apartments that sit next to I-81 in Syracuse. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

Detail view from under the viaduct. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

In a zero-sum game, there are winners and losers. The interstate traffic must go somewhere, potentially to nearby communities. Rejuvenating the area could bring prosperity, but also gentrification, pricing current residents out of their homes.

“What’s eerily similar to the original build is that those conversations were happening back then, too,” says Lanessa Chaplin, an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union who has advocated for changes to the viaduct.

It didn’t have to be this way.

As the Black population in Syracuse grew at the dawn of the last century, discriminatory real estate covenants barred them from buying in most neighborhoods, concentrating them in the now-defunct 15th Ward.

In 1937, in the wake of the Great Depression, a “redlining” map issued by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation carved cities into areas of highest and lowest investment risks — green for “best” and red for “hazardous.” The 15th Ward was shaded in red, making it all but impossible to get a loan to buy there or improve a property.

By the 1950s, the community was low-hanging fruit when the government went looking for decaying areas to clear out after World War II, making way for public works projects like hospitals, student housing and highways — including I-81.

The cover of a 1963 CORE booklet. (Onondaga Historical Association)

The cover of a 1963 CORE booklet. (Onondaga Historical Association)

It became a vicious cycle. The noisy highway raining down smog depressed property values on the streets below. As property tax revenues fell, Dr. King Elementary School lost critical funding, became increasingly segregated and saw students underperform in test scores. That pushed property values down even more.

Census data for 1950* shows how Black residents were concentrated in the 15th Ward, which Interstate 81 bisected in the 1960s.

Each dot represents one person:

*Hispanic and Asian ethnicity data was not available in the 1950 decennial census.

Census data for 2019 depicts how demographics in the neighborhoods have shifted in relation to highway construction.

Each dot represents one person:

At its closest point, Dr. King Elementary School is about 130 feet from the highway.

NBC News recently recorded six minutes of sound at 10 a.m. from Dr. King Elementary School. During that time, 31 vehicles passed the school on I-81, including seven trucks.

“You had African American households concentrated in these neighborhoods and overcrowding and decades of disinvestment,” said Sally Santangelo, who runs the Syracuse-based nonprofit CNY Fair Housing. “That was intentional and systematic.”

But undoing the damage is easier said than done. In 2019, a lengthy environmental study by the state’s transportation agency explored various options to removing or replacing the structure and deemed many too problematic: A new viaduct could be built, but that would require bulldozing even more buildings. A proposed tunnel was deemed too unwieldy and expensive.

So the state ultimately backed a “community grid” plan as its “preferred alternative” to the aging viaduct. As envisioned, the elevated highway would be replaced by surface streets, distributing traffic throughout the surrounding area. High-speed interstate traffic would be redirected onto I-481, a partial loop bypassing downtown Syracuse.

It would also bypass Salina, just north of Syracuse, where Carmen Emmi runs a cluster of hotels just off I-81, where the steady flow of truckers and travelers props up dozens of roadside motels, restaurants and gas stations.

“We rely on 81,” Emmi says. “I understand the wrong that was done 60 years ago. I am all for a solution that works for everybody in the region, and not one or the other. We don't need another loser.”

One of the hotels managed by Carmen Emmi just off I-81 in Salina, N.Y. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

One of the hotels managed by Carmen Emmi just off I-81 in Salina, N.Y. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

There are no perfect solutions. The current plan envisions a new access ramp just a few hundred feet from Dr. King Elementary School, fueling new pollution concerns. Rerouting interstate traffic requires the state to seize more than 100 properties in whole or in part, including from homeowners in nearby Cicero.

And there’s no consensus on what should happen to the 18 acres that will be reclaimed where the old viaduct now sits. Should it be set aside for affordable housing or a community trust, or zoned in a way that allows fancy new apartments or high-end businesses to move in? The state and a local transportation council have been debating that question for a decade.

Ryedell Davis, 35, sees both risk and opportunity in the former 15th Ward, where he grew up at Pioneer Homes and Central Village, public housing projects in the shadow of I-81. Family lore holds that his grandparents lost their restaurant to the interstate.

Ryedell Davis at his liquor store on the north side. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

Ryedell Davis at his liquor store on the north side. (Gavin Liddell / for NBC News)

These days, Davis runs a liquor store on the north side, but dreams of returning to start a new business — maybe an event space or the area’s first yoga studio.

“I just hope that it benefits the people who live down there,” Davis said. “When you start to own things inside of your community, you start to care about your community more.”

Tremé and the 7th Ward

New Orleans

Interstate-10, also known as the Claiborne Expressway

In New Orleans, a debate over an expressway that cut through the historically Black neighborhoods of Tremé and the 7th Ward blooms and withers with some regularity. Fiery rhetoric, careful analyses and plentiful plans have provided few results for a formerly thriving Black neighborhood, however.

Once called “the Main Street of Black New Orleans,” North Claiborne Avenue, from the early 20th century until the 1960s, was lined with white oak trees and a number of bustling Black-owned businesses: multiple drug stores, an insurance company, a theater, a toy store, numerous restaurants and a college for Black students.

THEN AND NOW view down North Claiborne at Ursuline Street. (Charles L. Frank Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection; Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

THEN AND NOW view up North Claiborne and Ursuline Street. (Charles L. Frank Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection; Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

But that all changed the day after Mardi Gras in 1968 when those landmark white oaks were ripped from the ground and replaced with sterile cement pillars that supported the I-10 expressway. Hundreds of residences and dozens of businesses along this vibrant economic corridor were destroyed.

Over the ensuing half-century, many have called for the expressway’s removal so that the neighborhood can return to its former glory. Amy Stelly, an urban designer, who lives in Tremé, leads that fight now.

The recent past has seen these historically Black neighborhoods suffer from blight and empty residences. Levels of poverty, violence and negative health outcomes have increased since the expressway’s construction. Stelly believes the only way for the New Orleans Black community to move toward renewal is through the highway’s removal.

“With urban highways intact, you get disinvestment, you see development occurring in suburban and rural areas — strip malls and other types of development that people go to but don't live around,” Stelly said.

After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005, the removal of the Claiborne Expressway was included in an early version of the New Orleans master plan and became a topic of debate from 2011 to 2014, when the city obtained a federal grant to invest in the Claiborne Corridor.

Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes, the director of the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, which supports Black artists and educators, said that many community advocates were initially supportive of the highway’s removal, but it soon became clear that residents in the affected neighborhoods were not as enthusiastic.

Residents were concerned with how it would affect real estate, which has been filling with short-term rentals trying to take advantage of the city’s rebounding tourist industry and the neighborhoods’ cultural capital. With Black renters forced out of their homes and the growth of Airbnbs in their place, advocates for and against the highway said gentrification already has a strong foothold in the neighborhoods.

“What became clear to us, we who work with the community and studied what has happened when these highways are removed, is that there’s an immediate and aggressive displacement of the existing community,” said Ecclesiastes, who has raised her five children along the corridor. “We decided the preservation of our neighborhoods and our cultural ties and traditions were more important than the interstate coming down.”

Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes with her family. (Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes with her family. (Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

Those opposed also cited costs as a concern: Estimates for the removal of the expressway run as high as half a billion dollars, and many in the area would rather see that money invested in affordable housing, flood protections, job creation and other efforts to maintain the neighborhood and its permanent residents.

The Port of New Orleans, a major local industry, was also skeptical about the purported travel alternatives, a sentiment shared by residents of New Orleans East’s Black neighborhoods who regularly used the highway to commute into the city.

Former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu said he came into office with the hope of taking down the interstate and reconnecting the neighborhoods. But Landrieu, who became known nationwide for his removal of the city’s Confederate statues in 2017, said he wanted to take a different approach and engage the community itself first. A $2 million survey in 2014 of the affected neighborhoods that analyzed the highway’s removal as well as other alternatives, such as investment in an economic corridor under the overpass, changed his view.

“It would be great if you could do it, but it takes a huge amount of money, planning and the commitment of the neighborhoods themselves, which was more complex than we originally thought,” he said.

With middling support for the project, Landrieu and many neighborhood advocates put their weight behind a rehabilitation effort for the expressway. The plan, which faces complexities because of zoning issues and challenges surrounding the structure of the expressway itself, pushes for the creation of businesses and investment in the oftentimes unused space underneath the highway.

Community members said the project’s regular planning meetings with city leadership have stalled somewhat during the pandemic and under the new mayor, Latoya Cantrell, who did not respond to a request for comment.

It has drawn federal attention, however, with the Biden administration specifically naming this corridor in its plan to address racism and highway infrastructure. Advocates on both sides of the debate are now dusting off competing health assessments and interstate plans for another fight about the future of these neighborhoods.

In the meantime, residents continue to use the space under the highway.

A brass band performs as a traditional New Orleans second line parade honoring “Uncle” Lionel Batiste, singer and brass drummer for Tremé Brass Band under the Claiborne Expressway in Tremé on July 23, 2012. (Erika Golding / Getty Images file)

A brass band performs as a traditional New Orleans second line parade honoring “Uncle” Lionel Batiste, singer and brass drummer for Tremé Brass Band under the Claiborne Expressway in Tremé on July 23, 2012. (Erika Golding / Getty Images file)

It’s not unusual for improvised cookouts and games of dominoes and cards to pop up on folding tables underneath the expressway. During Mardi Gras, the mixed sound of carnival revelers and brass bands reverberate and bounce through the highway’s columns. Pillars that replaced white oaks are now splashed with local artists’ renderings of New Orleans heroes and traditions.

Lancen-Keller, the Tremé resident, is the chairwoman of a local YMCA and said the neighborhood may have changed, but the culture is still very much alive and worth preserving.

Barbara Lacen-Keller under the Claiborne Corridor leaning against one of the pillars with a painted tree. (Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

Barbara Lacen-Keller under the Claiborne Corridor leaning against one of the pillars with a painted tree. (Annie Flanagan / for NBC News)

“As African Americans, we have to hold onto what is ours, and Claiborne Avenue, no matter what you do, will always be ours,” she said. “People talk about taking down the highway, but I think we need to keep making it our own.”

Boyle Heights

Los Angeles

Interstate 5, Interstate 10, U.S. 101, State Route 60, Long Beach Freeway

Once described as a “United Nations in microcosm,” the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights before World War II was home to Jews, Japanese Americans, Latinos, Black Americans, Russians and others. The subsequent internment of Japanese Americans, racist housing policies and eventually highways changed all that.

The immigrant and working class community has a long history of activism, first through unions and later through the Chicano movement of the 1960s. But it wasn’t enough to prevent decades of highway construction from the mid-1940s to the 1960s that plowed through and cleaved the community, demolishing homes, blocking residents from their churches, evicting homeowners and renters, and increasing pollution.

Aerial photo showing construction of a stretch of the Pomona Freeway from Boyle Heights to unincorporated East Los Angeles. (Courtesy Barrio Planners Inc.)

Aerial photo showing construction of a stretch of the Pomona Freeway from Boyle Heights to unincorporated East Los Angeles. (Courtesy Barrio Planners Inc.)

“It was with the freeways that Boyle Heights transitioned into a concentration of Mexican American or Mexican immigrant poverty,” said Eric Avila, an urban history professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Before the highways, the neighborhood “reflected multiracial, multicultural diversity and people creating a community together. … They worked through each other’s differences to build a vibrant, working-class neighborhood.”

Boyle Heights was officially deemed in the 1930s by the federal government to be a slum and “thoroughly blighted.”

“It was a neighborhood where the government felt that it was appropriate for the placement of unwanted infrastructure,”Avila said. “It didn’t matter if it impacted property values, because property values were already considered low to begin with.”

Los Angeles built only 61 percent, or 918 miles, of the freeway grid it laid out in a 1958 master plan, according to Gilbert Estrada, an urban historian and assistant professor at Long Beach City College.

The freeways it didn’t build, such as Beverly Hills Freeway, would have cut through white neighborhoods. It built 100 percent of the freeways planned for communities in East Los Angeles, however.

“Unlike the people of Boyle Heights, who protested against five freeways, the people of Beverly Hills won their fight against one freeway. That’s inequality in about as stark a picture as you can get,” Avila said.

Homes next to the freeway in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

Homes next to the freeway in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

From the start, opposition from Boyle Heights residents and local businesses was as fervent as that of the residents of Beverly Hills, but their political power was no match. As a result, Boyle Heights became home to the East Los Angeles Interchange — a 27-lane confluence of six freeways that blocked 32 streets and became known as “the Spaghetti Bowl, because it’s such a mess,” Estrada said.

“It’s so big, it’s actually three interchanges,” he said, adding that the California Division of Highways would joke about giving drivers “an award for not getting lost.”

Before the pandemic, about 2 million vehicles a day, including diesel trucks, traveled on the interchange, spewing exhaust and sickening residents in Boyle Heights and unincorporated East Los Angeles, according to Estrada’s calculations of 2017 California transportation data.

The Pomona Freeway sliced through Santa Isabel Church and its elementary school. Both were demolished in 1958 and then rebuilt farther from the highway.

Frank Villalobos attended the elementary school and saw the highway block his family’s path to Resurrection Catholic Church, where they attended Mass on Sundays and where his siblings went to school.

The highway construction in Boyle Heights also obliterated his childhood home, a Spanish colonial three-bedroom, two-bath that was the incarnation of his mother’s dreams, made real by his architect father’s artistry.

With an added den, kitchen cabinets that his father crafted and garden trellises, their home stood kitty-corner from the playground where Japanese, Jewish, Black, white, Mexican American and immigrant children played.

“It’s under a freeway now,” Villalobos, 75, the president and owner of the architecture and urban design company Barrio Planners Inc., said. “It was taken by a freeway. The entire neighborhood was taken.”

Frank Villalobos near the Pomona Freeway in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

Frank Villalobos near the Pomona Freeway in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

Today, about 4 percent of the city of Los Angeles and 1 percent of the county is covered by freeways. In Boyle Heights, that figure is about 12 percent, and in East L.A. about 19 percent, Estrada said.

For those who were evicted there was little place to go except public housing, rental homes in Boyle Heights and other redlined neighborhoods. Deed restrictions made many neighborhoods open to whites only, until the state outlawed such restrictions in 1957.

The government paid about $12,000 to homeowners in Boyle Heights at the time, which was about $5,000 less than the value of Villalobos’ home because of the improvements made by his father, “which is why my dad was probably the last one to move out of there, because he kept arguing the unfairness,” Villalobos said.

He wasn’t alone in fighting for some parity. In 1949, residents elected Edward Roybal, a Boyle Heights local, as the first Mexican American to serve on the 15-member Los Angeles City Council since 1881. Outnumbered, Roybal, who later went on to serve 30 years in the U.S. House, shifted to fighting smaller battles — such as for on and off ramps and for better compensation and housing for homeowners and the displaced, said George Sanchez, a University of Southern California professor of American studies and ethnicity and history.

“It was done in a very undemocratic way. The local population could do virtually nothing to change the plans, since it was a state-driven, appointed commission that could not be overturned,” said Sanchez, author of “Boyle Heights: How a Los Angeles Neighborhood Became the Future of American Democracy.”

In spite of the incisions it suffered, Boyle Heights remains a vibrant community that is home to many immigrants and Latinos. Murals, mariachis, panaderias (bakeries), a historic pharmacy and the use of Spanish all persist. The freeways have become integral to protest art and culture.

Traffic on the freeway near Soto Street Elementary School in Boyle Heights on June 16, 2021.

Pollution from vehicles, an abandoned battery recycling plant and other industry, as well as vulnerability to powerful political forces, are still problems, but the latest threat is a new form of displacement: gentrification.

A light rail system that opened in 2009 brought new transportation opportunities to Boyle Heights but also more attention from outsiders looking for cheaper rent and a diverse neighborhood. That has meant growing housing costs that price out low-income renters who are about three quarters of the neighborhood’s residents.

While there is no talk of removing highways that run through Boyle Heights, an L.A. County plan to widen nearby Interstate 710 that runs through Latino neighborhoods has been put on hold amid opposition and environmental concerns, including from federal and state officials.

Estrada said Boyle Heights is in need of sound walls that it didn’t get when the highways were built, as well as air filtration, cleaner cars and other improvements.

“It will be interesting to see where towns try to build, if there is a giant infrastructure plan under Biden,” Avila said, “and whether some of this kind of targeting of lower income neighborhoods gets repeated.”

Children play by an ice cream shop surrounded by murals in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

A musical instrument store in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

Mariachi Plaza in Boyle Heights. (Rozette Rago / for NBC News)

Graphics data sources:

Google Earth; Redlining area data from Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, NathanConnolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed.

Race and ethnicity data for 1950 and 2019 comes from IPUMS National Historical GIS, University of Minnesota.

The 1950 population and housing figures come from the decennial census. Population counts for that year were determined from census tracts, which are subdivisions of a county that contain 1,200 to 8,000 people and cover a contiguous area. Hispanic ethnicity data was not available in the 1950 decennial census. "Other" means people who weren't identified as white or Black.

The 2019 figures are estimates from the Census Bureau's five-year 2019 American Community Survey. Population counts that year were determined from census block groups, which are clusters of 600 to 3,000 people that don't cross state or county boundaries. Black, Asian, other race and white categories exclude those with Hispanic ethnicity since any race can have Hispanic origin. "Other" includes multiracial and other race census categories.

Graphics and development:

Jiachuan Wu and Robin Muccari

Photo editing:

Shahrzad Elghanayan

Video editing:

Brock Stoneham