SILVER SPRING, Maryland — It’s hot and sticky in Silver Spring in June, and the mosquitoes are everywhere, breeding at construction sites, in backyard ponds and in the swampy pools left behind by two weeks of torrential rains.

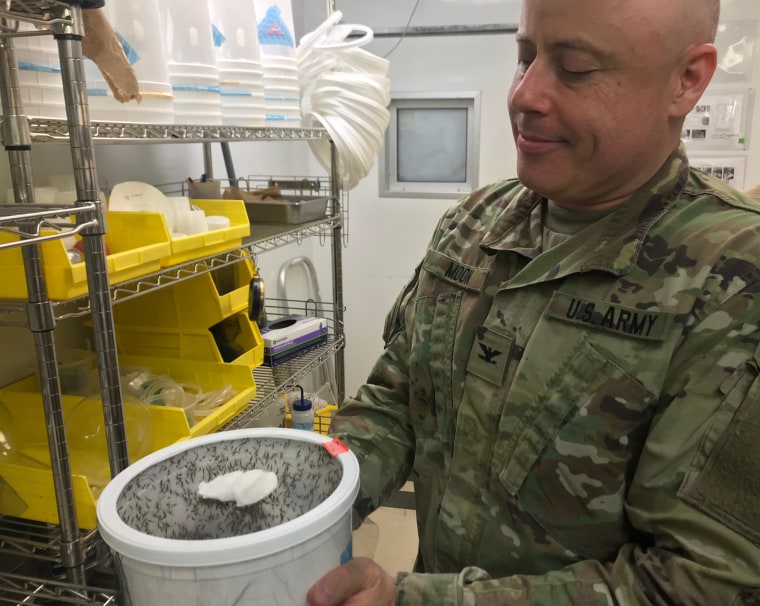

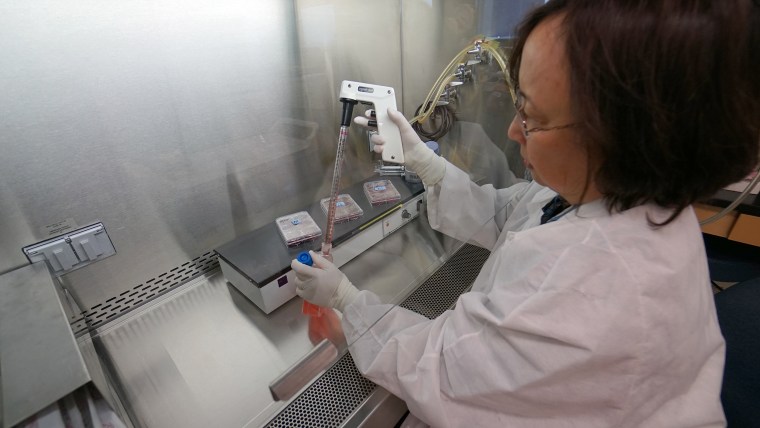

It seems unthinkable that anyone would be breeding more mosquitoes on purpose, but deep inside the blue-and-yellow Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Lindsey Garver and her colleagues are breeding them by the thousands and feeding them human blood.

They are Anopheles — the mosquitoes that spread malaria. One of Garver’s jobs is to make sure these insects get infected with the Plasmodium falciparum parasite that causes malaria.

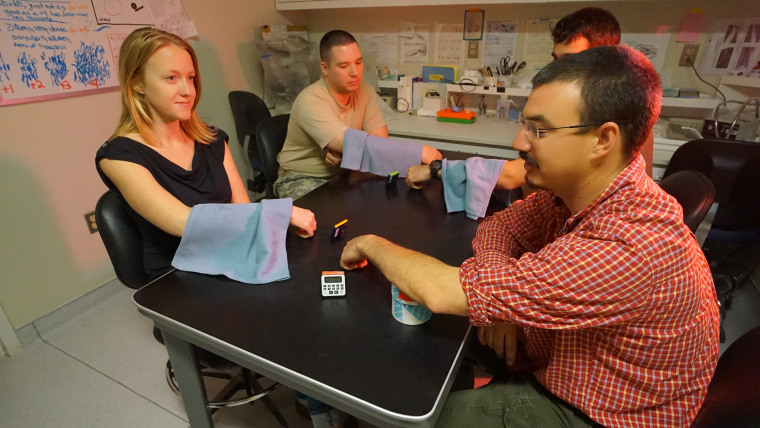

Then they’re letting them bite people.

Most of the volunteers who have been bitten by the mosquitoes have also been vaccinated with a malaria vaccine. The hope is to find a better dose or a better dose regimen that will get better than the 30-40 percent protection the vaccine currently provides.

But 38 of them have not been vaccinated. They’re the controls.

The vaccine development team needs for these people to come down with malaria, to show the mosquitoes really did transmit the parasite.

“I am hoping we see 38 people develop infections,” said Dr. James Moon, an Army colonel who’s leading the vaccine study.

And he hopes all 130 volunteers who got vaccines before exposing the tender undersides of their forearms to the hungry mosquitoes will not get infected.

Malaria infects more than 200 million people a year, the World Health Organization says. It killed 445,000 in 2016, mostly children.

The parasites that cause malaria set up a complex life cycle in the human body. While some are easily killed with modern medicines, in many regions the parasites have developed resistance to most of the drugs on the market.

Widespread use of insecticides eradicated malaria from the U.S., but the fight elsewhere has been tougher.

People can take drugs to prevent infection, but malaria is a disease of poverty. Malaria is an everyday threat across much of Africa, Southeast Asia and South America. Most of those susceptible to malaria have almost no access to drugs either to treat it, or to prevent it.

A vaccine would be the best solution. Only one is in use — Mosquirix, or RTS,S. GlaxoSmithKline worked with the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative to develop the vaccine, and now the Walter Reed team is testing it to see if they can make it work better.

There are indications they can. Tests on more than 15,000 babies aged 6 weeks to 17 months old showed close to half of them — 46 percent — were protected from malaria for 18 months after they got a three-dose series of the vaccine.

A rival vaccine made by a company called Sanaria, in the past also supported by PATH and WRAIR, protects 55 percent of people who have tried it in experiments.

That doesn't sound like a great result, but even partial efficacy can save tens of thousands of lives.

This study of Mosquirix at Walter Reed aims to see if various doses, given at various times, can protect adults more effectively or for longer periods.

“We are trying to find the best pattern to get the best antibody responses,” Moon said.

“It could be that if I give you fewer doses (it will work better),” he added. ”Or maybe fewer doses will have the same efficacy as the current regimen. That would save money and simplify the process.”

It’s also possible that waiting for longer or shorter periods between vaccine doses and boosters will improve efficacy.

People have to be exposed to real malaria because there is no blood test that can show whether a vaccine has elicited the desired immune response. So last fall, Walter Reed recruited people living in the area to volunteer both to be vaccinated and to be bitten.

“This is the largest challenge that’s ever been done,” Moon said.

Who would volunteer to be bitten by mosquitoes, let alone those that guaranteed to transmit malaria? Especially when the disease is no threat locally?

Plenty of people, said Garver and Moon. Most are motivated by the desire to help others.

“We have had people put their mosquitoes on Instagram. Some people really enjoy doing this. They have altruistic motives,” Garver said.

And anyone who develops malaria will be treated for it. These tests involve Plasmodium falciparum.

“This is a highly susceptible strain,” Moon said. “Anything can kill it.”

Malaria is notorious for staying in the body and coming back at inconvenient times, but that’s malaria caused by different species — Plasmodium vivax or P. ovale, Moon said. Once P. falciparum is treated adequately, it’s gone.

One main challenge is getting the mosquitoes to actually bite some of the volunteers. Some people just don’t smell tasty to the insects. “We have different tips and tricks when that happens,” Garver said. “One of those is sweaty socks.”

Mosquitoes are especially attracted to human foot odor. “We have had people rub their foot on their arm,” she said.

The vaccine is designed to stop the parasites before they get into the liver.

An infected mosquito injects Plasmodium sporozoites into the human’s bloodstream when she takes a blood meal. These sporozoites travel to the liver and develop for a while, multiplying before they go back into the blood and infect red blood cells. None of this causes symptoms.

“The symptoms occur when they burst out of the blood cells,” Moon said.

Then people develop fever, chills, sweating and the other unpleasant and often deadly symptoms of malaria. And that’s when people can infect more mosquitoes that bite them.

Malaria’s complex life cycle makes it hard to fight, but it also is what makes it possible to eradicate it.

For malaria to circulate in people, you need the right species of mosquito — Anopheles. In addition, many people must be infected with malaria. The mosquitoes have to bite infected people, and they must survive long enough for the parasites to develop in their bodies and get into their salivary glands.

“A lot of factors have to fall into place to have them transmit malaria,” Garver said.

And a lot of factors must fall into place to get rid of malaria. “To eradicate it, we are going to need more than just one method,” Moon said.

“A vaccine is one tool.”